Community development is “about giving the choices back to the community” says Izzaty Ishak, a theatre-maker and community worker with Beyond Social Services.

It’s 7pm on a Friday at the Leng Kee Community Centre. I am sitting with Izzaty when two young members of The Community Theatre (TCT) enter carrying 10 boxes of curried chicken cooked by their mother, a resident in the nearby rental flat community of Lengkok Bahru. They arrange the boxes in a circle and invite us all to sit and makan.

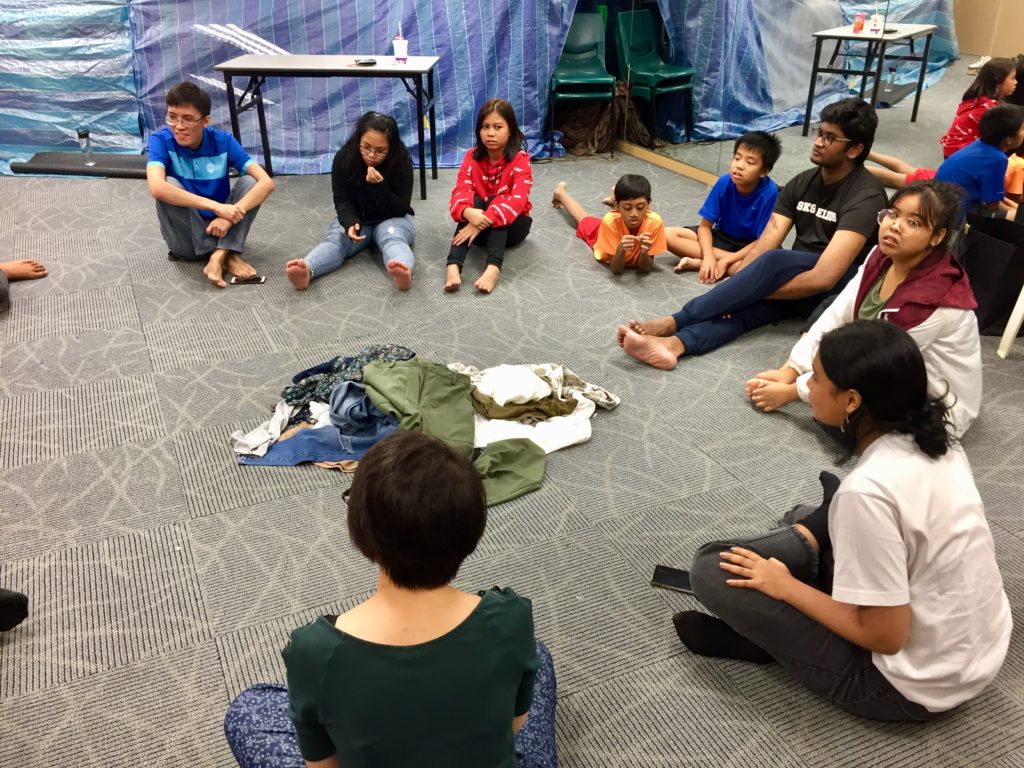

In the centre of the circle is a pile of recycled items – second-hand clothes, makeup, shoes, a plastic safety helmet – that will feature in today’s rehearsal. TCT members will be leading a photoshoot to brainstorm for the marketing of their upcoming devised performance about poverty that will feature in the M1 Peer Pleasure Youth Theatre Festival next year. Izzaty gives the young theatre-makers a prompt to which they are to respond visually. She invites them to brainstorm various possible endings to these sentences: “people in poverty are…” and “people in poverty are not…” and then to curate a series of photographs that represent the sentences.

A Strengths-Based Approach to Community Development

TCT is an initiative by Beyond Social Services (BSS), a voluntary welfare organization that helps underprivileged youth in Singapore break away from the poverty cycle. By providing resources, support, and care, BSS empowers families and communities to guide their youth away from delinquency and towards holistic well-being and success. BSS takes a strengths-based approach to community development, believing that every human being has hopes, concerns, and the capacity to contribute to her/his community. As such, their work focuses on highlighting and celebrating the gifts of a community, empowering them to use their own strengths in order to find innovative solutions to the challenges they face.

“We stop seeing our youths as participants, clienteles or even beneficiaries. We start seeing them as young people who can contribute, be volunteers or even leaders for their community.”

TCT’s work is motivated by the same strengths-based approach, explains Izzaty. “We provide a space for our youths where we see their experiences and stories as strengths or gifts to help others learn and reflect.” Oftentimes these stories are used to provoke sympathy or to ask for help but TCT “want(s) to disrupt that narrative.” “We stop seeing our youths as participants, clienteles or even beneficiaries. We start seeing them as young people who can contribute, be volunteers or even leaders for their community.”

TCT youth prepare for a photoshoot for a play about people in poverty.

The Community Theatre Process

TCT meets twice a week to devise, rehearse, and refine original work. Their performances emerge from the lived experiences and stories of TCT members. The group comprises youth from rental-flat and purchased-flat communities, as well as several social workers and teachers. TCT has recently grown to a 30-person-strong group of committed members, thanks to what Izzaty calls the “contagious effect”, whereby people who experience TCT’s work want to join TCT, or even feel inspired to create similar theatre collectives in their own communities.

TCT’s devising process begins with a common stimulus, explains 16-year-old Rushaimi, who joined the group last year in order to realise his dream of acting. For example, the rehearsal might start with a prompt like “you find S$1 million, what do you do?” and the youth “start(s) improvising and brainstorming from there.” The emphasis is on sharing personal stories, even if this process can at times be vulnerable and difficult. 14-year old Arif explains that – even though he joined TCT in order to express himself and “make others feel how (he) feel(s)” – storytime is the most challenging part of TCT. Arif says that “it’s damn hard for (him) to share (his) story with others” but that with the encouragement of fellow TCT members, he feels able and willing to share.

TCT member Rushaimi models for a photoshoot about the contradictory messages that people living in poverty often encounter.

Interactive Theatre: A Space for Exchange

Izzaty and her colleagues seek to create spaces for exchange and story-sharing in both rehearsals and performances. Izzaty would loosely categorise all of the work that TCT does under “interactive theatre” wherein the audience is somehow involved in the performance, creating a conversational loop between audience and performers.

Whether through forum theatre – whereby the audience is actively involved in intervening in the direction (and eventual outcome) of the story – or through performative-workshops – whereby the audience members are suddenly included into the space as actors – the performance experience becomes an opportunity to facilitate a bridging between otherwise disparate groups of people, as audiences often comprise a mixed group of rental and purchased-flat residents. By fully engaging and including the audience, Izzaty explains, their diverse personal stories and ideas become part of the performance space. This provides an opportunity for valuable (and rare) moments of exchange – a central process for community development.

Izzaty recounts a particularly fond memory of a Theatre In Education event that she facilitated in collaboration with students from Singapore Polytechnic. The event was intended as a volunteer appreciation programme centred around questions of ‘successful volunteerism’.

The event involved a pre-workshop, a performance, and a post-workshop. During the pre-workshop, participants (comprised of volunteers who come from both rental and purchased-flats) discussed what it means to be a ‘successful’ volunteer. After watching a short performance featuring similar themes, they participated in a post-workshop of ‘hot-seating’ wherein they interviewed and advised the characters from the performance on various dilemmas that they were facing. The post-workshop surfaced important disagreements that built empathy by “enrolling the audience into the performance space” and inviting them to speak from personal experience.

In one instance, for example, several audience members proposed advising the character to sacrifice her hobbies in order to focus on studies, accept her difficult circumstances and focus on empowering herself to move forward, rather than continue to dwell on her misfortune. Another group of volunteers – mothers from a rental-flat community – stepped in to disagree, explaining how the character had already sacrificed so much to get to that point, and that it was unrealistic and unreasonable to ask her to give up her hobbies too.

“Their personal stories become a strength, an opportunity for them to educate other people.”

“The rental-flat mothers realised that these characters were them, last time,” explains Izzaty, “so their personal stories” and experiences – traumatic as they might have been – “become a strength in the space, an opportunity for them to educate other people.” By providing a space for rental-flat volunteers to speak from a place of strength and expertise, the post-workshop challenged the power dynamics that are common in situations where different socioeconomic classes are represented.

In all of TCT’s work, it seems, the focus is on empowering individuals to realise the value of their personal experiences and stories. Stories are assets that are central to empathy building, effective communication, and ultimately – community development.

Sharing Ownership

Success, for Izzaty, is when older TCT members ask her to pause rehearsal so that they can explain the instructions for an activity to a younger TCT member, or when they excitedly tell her that they have an idea for a performance, and that they want to start writing the script. The more TCT members have ownership over the direction of TCT, the better.

By sharing ownership of TCT, Izzaty also invites TCT members to share responsibility for each other’s well-being. “We have to accept that this is more than just theatre,” says Izzaty and that “a lot of people are going through difficult things in their lives.” By connecting people to each other and building networks of support in and outside of the rehearsal space, community is being developed and strengthened.

As young a company as it is, TCT seems to be very successful thus far at making people feel supported, connected, and valued. Rushaimi says that TCT is the most important community that he has, and Arif explains that TCT exists to “help everyone get to know about their own community.”

14-year old TCT member Qistina agrees. She says, “my favourite time at TCT is every session at dinner time, when everyone will sit together and eat, then share our problems, talk to each other, and make a lot of jokes […] this is a community because we share our personal stories with each other and we don’t keep secrets.”

A devising process underway at The Community Theatre rehearsal.

Moving Forward

Izzaty believes that the TCT approach to community development can be adopted by any community. What is essential, however, is to start with simply building relationships. One must start by discovering the strengths that are present within a community and exposing the community to art in order to “let them explore if art is meaningful for them” says Izzaty. From there, community development can occur through an iterative and scaffolded process involving “exposure, experience, reflection, and embodiment of art.”

A research study commissioned by BSS earlier this year found that BSS community engagement initiatives that involved consistent and regular programming over a long-period of time (like TCT) resulted in an increase in youths’ sense of their personal and collective safety, the health of their neighbourly relationships, their ability to manage conflict and familial problems, and their overall sense of happiness and empowerment in life. By offering a dependable, safe, supportive, and empowering space, Izzaty and her co-creators at TCT are giving choices back to communities, inviting each and every person to be part of decision-making on how to move forward.

Feature photo: Publicity photo from TCT’s “One More Light” production. Photo by Asnur Asman.

Images if not specified are by Kei Franklin.

About The Community Theatre

The Community Theatre is an initiative by Beyond Social Services that rallies volunteers from different walks of life to co-create a show that engages its audience to reflect on the social challenges faced by children and families from low-income backgrounds.

Since 2015, The Community Theatre has developed into a youth development programme that engages both rental and purchased-flat youths to produce interactive performances base on personal experiences. These performances are toured to various rental flat communities which enables youth volunteers to contribute back to their own community despite their challenging situations. Through these performances, audiences are encouraged to contribute their thoughts about the issues at hand through a safe and interactive experience of theatre.

About the writer

KEI FRANKLIN believes strongly in the power of creativity, community, and constructive conflict to change culture and enact positive social change. A graduate from Yale-NUS College, Kei now works at Skillseed, where she crafts and curates socially-impactful experiential learning journeys and conducts trainings in social-emotional competencies and social innovation frameworks. She is a facilitator at Climate Conversations and an editor and writer for Brack magazine – a platform for socially-engaged art in Southeast Asia.