Library / Field Studies

Exploring the Social Curating and Archiving Project

Library / Field Studies

Exploring the Social Curating and Archiving Project

A Critical Reflection on Shaping a Participatory Platform for an Ageing Community in Whampoa, Singapore

As an architect, educator, and an alumnus of Cranbrook Academy of Art and the National University of Singapore, I am a strong advocate for an art-design nexus pedagogy and practice. Although the two fields have different outcomes and appear irreconcilable, the convergence of methods, media and contemporary issues has reduced the gulf. Artists increasingly use designerly ways of thinking and approach in their practices, while architects and designers have deployed art strategies in making and socially-oriented projects.1 I am fascinated by the discursive nature of design. It opens enormous opportunities for critical and speculative projects, raises awareness, provokes reflection, and challenges one to question assumptions. Naturally, I am drawn to socially engaged art projects for their discursive and activistic nature. By orienting design as discourse, it binds design education and one’s creative practice in an entangled relationship with the arts, ecological, sociocultural, economic, and technological concerns while broadening the designer’s role in society. The social curating and archiving initiative is my attempt to weave the art-design nexus ethos into my teaching and practice.

Social Curating and Archiving

During one session listening to the stories of an elder’s collections in 2018, the preliminary concept of social curating and archiving was conceived. Jessie is single, and she was moving to a studio apartment for seniors and selling her current flat. She planned to discard most of her collections, as the apartment was much smaller and had less storage space. Donating them to the museum or archive was also not an option. They were ordinary items with no historical value or meaning beyond her immediate, personal history. Although the profit from the flat’s sale enabled her to live her remaining years comfortably, she was torn between having to discard her collections and meeting her financial needs. During a brainstorming session with my collaborators, we decided to reach out to organisations in Singapore that might be interested in her collections.

Jessie shares stories of her collections at her home.

The Asian Film Archive responded to our appeal. They were keen to digitise Jessie’s collection of old movie magazines, posters, and newspapers. We organised a curating and archiving session at Jessie’s home where she could decide together with the archivists which magazines she would like to be digitised and determine what to discard or give away. The process of curating and archiving her collections provided an opportunity for Jessie to share her stories of growing up as a fan of old movie stars and Chinese opera performers from Hong Kong and Taiwan. The archivists were gratified to speak with someone who had first-hand knowledge of some of the Chinese opera performances held during the early years of Singapore. Besides collecting old movie and Chinese Opera ephemera, Jessie had also amassed a large collection of objects and ephemera during her employment with a local departmental store. It was her first and only job after leaving school at an early age to help support her family. During her years of service, she collected different shopping bags, promotional materials, objects, and even photographs of an annual festive party at the home of the departmental store owner. We contacted the current CEO of the departmental store, the son of the owner, and he agreed to meet Jessie at her home. The occasion was a memorable and poignant one. Seeing Jessie recounting her time as an employee and memories of working in the store was a touching moment for all of us. She went through her collections carefully and talked about the stories behind them. Most memorable of all was when Jessie spoke about an annual event held at the departmental store owner’s home while showing his son, the current CEO, a slightly worn photograph of the staff taken by his father during the event. The meeting ended with Jessie giving back the objects and ephemera to him. When asked how she felt about the whole experience, Jessie’s reply was striking. She was glad that she had the chance to decide whom she was giving her collections away to. She had agency in determining the next life of her collections instead of leaving them to her next of kin to sort, give or dispose of the collections when she passes on. Equally important, the process of social archiving enabled her to connect with an individual who had a strong relationship to her former working life, to recollect and share her past experience with him, and to leave behind a legacy of working at the departmental store. It gave her a chance to part with her collections, knowing that they will be cherished beyond her lifetime.

Social curating and archiving is a new, experimental practice that combines giving, safekeeping, storytelling, and the renewal of a place or a collection. It can take place through a simple in-person ritual in Jessie’s case, as an in-place public event or a digital interface to sustain the social life of the collection beyond the individual. Unlike the institutional form of curating and archiving, I see this new model as participatory art-making, forming new social relationships in the process of transferring or giving away a collection. It is potentially a scalable practice ranging from an intimate living room setting to a large, community-level interaction.

Archive and the Arts

Over the years, archives have provided artists and educators a creative platform for the production of art and an alternative way to investigate urban spaces and activities.2 In Archival Art: Memory Practices, Interventions, and Productions, Kathy Carbone argues that artists use archival art as a medium to critically examine the questions of memory, history, and meaning-making and present new interpretations through counter-narratives from the officially sanctioned versions.3 Similarly, the concept and purpose of the archive have been re-examined, critiqued, and reframed. French philosopher Jacque Derrida’s Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression puts forth the argument that how something is archived also influences its reception and relationship to the future.4 In his essay Archive and Aspiration, anthropologist Arjun Appadurai asserts that archiving is a collective social project. It is not neutral, but an intervention and an act of imagination in anticipation of collective memories.5

In his 1998 book Relational Aesthetics, curator Nicolas Bourriaud reframed the artist’s role as a facilitator for social exchange.6 Art-making goes beyond the sole authorship of the artist and the confines of the artist’s studio. The viewer as a participant plays a significant role as well. The artwork becomes a medium for forming human relationships, while the aesthetic is the experience of interaction. In the social archiving session between Jessie, the archivists from the Asian Film Archive, and the son of her former employer, she was an active participant in different ways. Jessie shared stories of her collections, co-deciding on the film ephemera she planned to digitise, gave part of her collections to the departmental store, and served as a generous host for the social curating and archiving experience. The forging of a relationship between Jessie and her guests was an aesthetic experience shared by all. The encounter with art became part of an everyday experience in Jessie’s home. The actions of curating and archiving and their institutional relationships are less clear. Whether it is learning the skills of curating and presenting in public their favourite recipes by the Whampoa elders in an earlier event held at the Whampoa Community Club, or Jessie’s experience of sharing and archiving of her collections, the process is a collective, participatory, and an aspirational journey that builds capacity, encourage intergenerational learning, and renews the life of a collection.

Social Curating and Archiving as Placemaking

In 2020, I ran an elective module on Social Curating and Archiving in the Department of Architecture at the National University of Singapore. It drew heavily on the ideas of curating and archiving as a socially engaged practice and my experience gained from working with Jessie. Opened to students from architecture, urban design, and planning, the module provided a series of learning scaffolds and required the use of different platforms and media. Students also had to engage directly with elders through in-person interviews. The goal was to design a space in Whampoa where the archive can become a place to present and share the elders’ collections and promote intergenerational learning.

As an icebreaker, I introduced the Circle of Giving, Sharing, and Caring exercise on the first day of class. Students brought a small gift that carried a personal story for a fellow student. During the gift-giving session, each student spoke about how the gift related to a moment in his or her life. The gift receivers were required to safely keep the gift, share how it became part of their lives over the thirteen-week semester, and pass the gift to another person outside the group. More than half of the students were international students from different parts of Asia. The stories shared over the gifts revealed the diversity and common personal experiences of growing up in their home countries. It helped build greater awareness of and sensitivity to each other’s unique and shared place in the world.

During the semester, the students interviewed the elders from Whampoa on their collections of cherished objects. The interview was an essential component of the pedagogy and the process of designing a social archive that the residents could sustain. The dialogical experience and the chance to interact with the objects weaved the spoken word with the tactile and the material. The preciousness in which the elders held some objects signalled the care needed in housing them. Originally, the students and elderly participants had to co-design the social archive and showcase their collective efforts in a public presentation. However, the rapidly escalating pandemic made it impossible to carry out.

A Whampoa elder sharing a story of her watch with the architecture students.

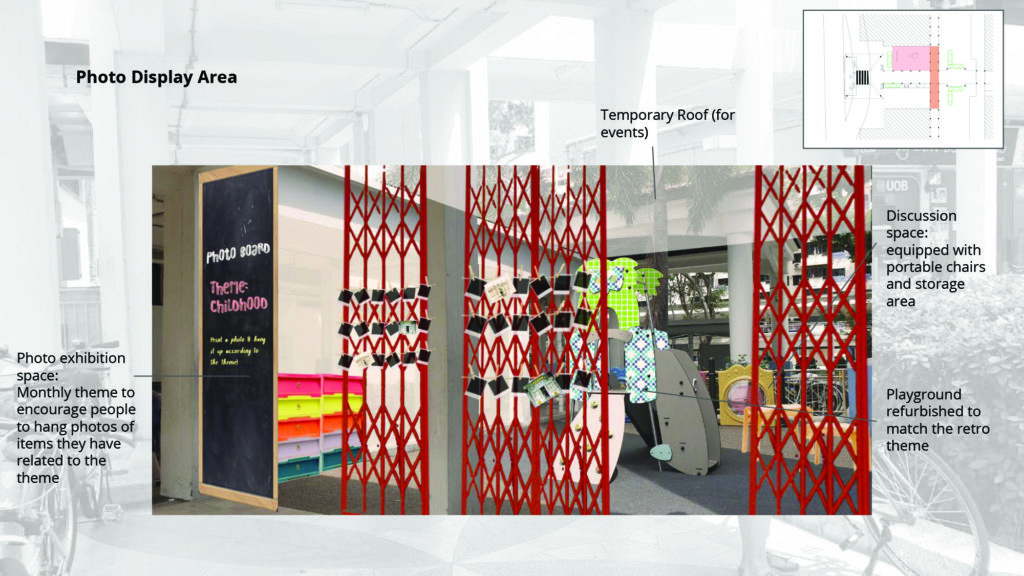

Architecture students Grace Ng and Seow Wei proposed the expansion of an outdoor playground to include an archive that showcased the daily lives of Whampoa residents through photography. The playground is a popular spot for children, grandparents, and domestic helpers who accompany the kids to school. Being close to the bus stop, the playground is also a social space for the residents. A new roof over the space allows for all-weather use and exhibits the works from the proposed photography workshop on a rotational basis. Along the passage from the bus stop to the social archive, the students designed several changing theatrical settings, incorporating photos from the participants as Instagram corners for the younger Whampoa residents.

Social Curating and Archiving: From Personal Possession to Public Legacy

The same year, I was awarded a grant from the National Heritage Board that allowed me to collaborate with my colleague Dr Lilian Chee from the National University of Singapore and Senior Lecturer Peter Chen from the Nanyang Technological University in expanding the personal possessions of Whampoa elder residents to a public legacy through the Whampoa Archives. It is designed to house the collections of objects and stories, works from the Curating Whampoa project, downloadable 3-D models of the objects, and a short film that features the relationship of six elders with their collections in their home settings. Led by Dr Lilian Chee, the film explores ethnographic filmmaking and empathetic technologies7 to capture nuanced relationships and gestures that escape static recording forms. Besides its archival function, the website allows visitors to contribute stories of their objects and for local schools to use as a teaching and learning platform. The project takes on a different challenge by building a public legacy from the elder’s personal possession on the internet. We see this as a necessary step with a growing number of people contributing and sharing online. The scalability and reach afforded by the internet were also important factors when we consider the potential public dimension of a collection. In this project, we are interested in broadening the material legacy afforded by the objects and the stories that narrate the lives of the elders.

In their study of fourteen adults from thirty-one to ninety-four years old, Elizabeth Hunter and Graham Rowles conclude that leaving a legacy helps a person to overcome the fear of death, provides the comfort that one’s life has a purpose and meaning, a chance to share one’s life experiences and the agency to shape how one could be remembered by future generations while still alive.8 Through our interviews with the elders during the Curating Whampoa and Social Curating and Archiving projects, we discovered many similarities between our experiences and the study of legacy by Hunter and Rowles. The objects were not only memory triggers. Beyond reminiscence and connecting to their autobiographical past, the objects enabled the elders to self-reflect and share values of thrift, hard work, overcoming adversities, and the importance of family bonds. On several occasions, different interviewees mentioned the same values. They saw their participation in the project as a way to transmit these values to the next generation.

Jessie’s remark that she was grateful for having control over how and who she gave her collections to during the curating and archiving event at her home reaffirms the study’s findings. Moreover, the re-telling of their life experiences was a personal narrative that traversed time and space and consisted of memorable events, places, and characters. During the intergenerational conversations between the design students and the Whampoa elders, they spoke about their objects and personal stories of migration, living and working in Singapore, starting a family, individuals who made a mark in their lives, and the challenges of growing old.

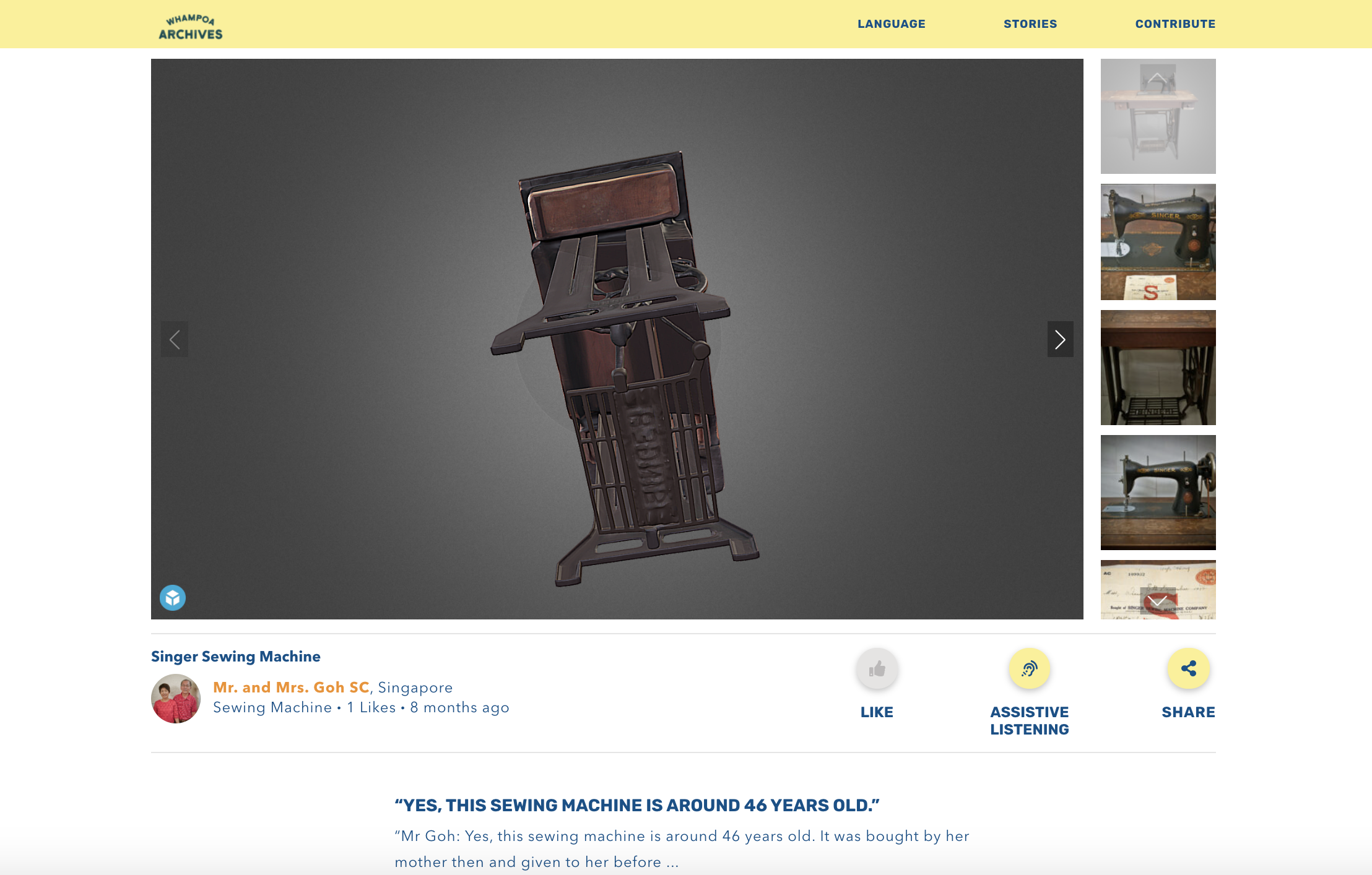

It is unimaginable for us not to interact with digital technologies and platforms in our modern-day society. Digital photos, videos, music, messaging services, and games are inseparable from our everyday lives. The Covid-19 pandemic has accelerated our pivot to a blended existence where the digital and the physical merge seamlessly. To remain relevant, many museums and businesses have also created virtual spaces because of the frequent lockdowns during the pandemic. What was a temporary solution has become an important complement to the physical experience. However, scholars have debated over such digital experiences. Many argued the limitation of a screen-based experience, and the absence and loss of materiality and authenticity when physical objects become digital. In Engaging the Materiality of the Archive in the Digital Age, Mark Tebeau debunks the myth of the virtual physical divide. Using examples from his practice, he argues that digital tools complement the materiality of the physical collections, amplify the experience, and open new, interpretative space.9 His defence of the digital could not be truer when an elder exclaimed she could rotate with ease the scanned digital model of her old sewing machine on the website. She was thrilled to see the underside of the cast iron stand, which would otherwise be impossible given its weight.

Archiving the collections online and a different relationship and experience with the objects.

Conclusion

Social Curating and Archiving started with a motivation to curate and present the Whampoa elders’ rich experiences and memories of living in Singapore. Each step of the process was an opportunity for critical reflection, discovering new possibilities and to test ideas, leading to the concept of social archiving as a participatory experience that builds capacity, encourages intergenerational learning, and renews the life of a collection in-person and digitally. Looking back, the peripatetic experience and insights gained through organising the myriad projects, conversations, and collaborations were vital in shaping the subsequent actions. The aims were clear even though the goals seemed uncertain at that time. Although the Whampoa Archives marks a significant milestone in formalising the concept of social curating and archiving, plans are already underway to set up workshops to train a community of curators and archivists among the Whampoa elders who will eventually take over and lead the project after 2022. As the project comes to a provisional closure, I recall the words of a dear friend and curator Mary Jane Jacobs, who wrote in her book Dewey for Artists:

The end of a creative process was not a “terminal point, external to the conditions that have led up to it”; rather, the end was “the continually developing meaning of present tendencies.” Then, ends become the means of propelling next stages within a sustained continuity of creativity and change.10

[1] Thomas Kong, ‘Between Making and Action-Ideas for a Relational Design Pedagogy’, in Emerging Practices: Professions, Values and Approaches, ed. by Jin Ma and Yongqi Lou (Shanghai: China Architecture and Building Press, 2015).

[2] Shiqiao Li, ‘Archiving Space’, in Kowloon Cultural District: An Investigation into Spatial Capabilities in Hong Kong, ed. by Esther Lorenz and Shiqiao Li (Hong Kong: MCCM Creations, 2014), pp. 156-164.

[3] Kathy Carbone, ‘Archival Art: Memory Practices, Interventions, and Productions’, in Curator: The Museum Journal, 63.2 (2020), 257-263.

[4] Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, trans. by Eric Prenowitz (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017).

[5] Arjun Appadurai, ‘Archive and Aspiration’, in Information is Alive: Art and Theory on Archiving and Retrieving Data, ed. by Arjen Mulder and Joke Brouwer (2003), pp. 14-25.

[6] Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics (Dijon, France: Les Presses Du Reel, 1998).

[7] Sarah Pink et al., ‘Empathetic Technologies: Digital Materiality and Video Ethnography’, in Visual Studies, 32.4 (2017), 371-381.

[8] Elizabeth G. Hunter and Graham D. Rowles, ‘Leaving a Legacy: Toward a Typology’, in Journal of Aging Studies, 19.3 (2005), 327-347.

[9] Mark Tebeau, ‘Engaging the Materiality of the Archive in the Digital Age’, in Collections: A Journal for Museum and Archives Professionals, 12.4 (2016), 475-487.

[10] Mary Jane Jacobs, Dewey for Artists (Chicago, United States: University of Chicago Press, 2018).

All images provided by Thomas Kong, except otherwise mentioned.

Cover Image: Jessie’s collection of old movie magazines. Photo credits to Peter Chen.

About Thomas Kong

Thomas received his architecture degree with honours from the National University of Singapore, and a Master of Architecture, with distinction from Cranbrook Academy of Art, USA. He is a licensed architect in Singapore and an associate member of the American Institute of Architects. Thomas has over 20 years of experience teaching architecture, interior architecture, and advising students in the MFA programme in Chicago, Toronto and Singapore. Thomas’s interdisciplinary practice and research are centred on art-design nexus. He has received awards and grants from Finland, the Netherlands, the U.S., and Singapore, and has lectured and published internationally on the intersection of art and design education.