Library / Field Studies

An Interview with Janet Pillai

Library / Field Studies

An Interview with Janet Pillai

To those who have been to our Greenhouse Sessions or cultural mapping workshops, Janet Pillai is no stranger. In the domain of cultural and community research and practice, Janet is an expert. So when the opportunity for an interview arose, we jumped at it.

How did you get into the work of cultural mapping and creative placemaking?

When I started my career as a theatre director after graduation, I was drawn towards forms such as theatre for development and people’s theatre. For several years, I experimented with an approach to devising theatre that was based on research in real communities. I often collaborated with artists and NGOs who were already familiar with the community context and specific social issues. In early 2000, Georgetown, which was where I was working, experienced a severe downturn that threatened its cultural heritage. The crisis situation led me to formalise an organisation, Arts-Ed, to promote heritage awareness and cultural sustainability among children and adults residing in the site. Being outsiders, we needed a more holistic understanding of the cultural ecosystem before tackling the revitalisation of the town’s endangered cultural assets. Inevitably, we stumbled into cultural mapping, and then into creative placemaking. During the 10-year journey that was to follow, Arts-Ed worked with partners such as NGOs, historians, conservation architects, urban anthropologists and artists on the ground to try and embody these concepts.

Tell us about your most meaningful/successful creative placemaking project.

The Chowrasta Market Upgrading Project in Penang was conducted by a multidisciplinary team consisting of researchers, architect-designers, market vendors and municipal authorities. A healthy negotiation and knowledge exchange process developed between the creative practitioners and users of the site through repeated cycles of research, analysis, and consultation.

Through this process, the community began to better understand the needs and limitations imposed by space, finances, engineering and health regulations. The designers, in turn, began to recognise the market vendors and traders as a historically practising community with its own set of cultural knowledge, competencies, and resources. Arts-Ed acted as mediators and discovered how genuine public engagement and consultation could unlock the potential of placemaking; when there is a shared aim, placemaking can generate social cohesion and respect for different types of knowledge and skills.

What does creative placemaking mean to you?

I view placemaking as a transformative process that facilitates the eventual revitalisation of urban or rural settlements and ecosystems that are facing impediments or decline. ‘Creativity’, in such a process, refers to innovative strategies to manage and rebuild cultural citizenship along with social and economic infrastructure.

While attempting to unearth Georgetown’s 100 year history, I realised that placemaking is both a creative and adaptive process. It naturally occurs when people interact with new environments, urban or rural, to forge new social relations and livelihoods. Cultural adaptation, or the ability to creatively blend the known with the unknown, the old with the new, is a kind of creative force that generates cultural energy. This energy, in turn, facilitates placemaking and develops robust human settlements.

“Placemaking can act as a catalyst in rebuilding social relations, improving economic opportunities, reactivating systems or restoring the environment.”

When and why do you think placemaking is important?

Creative placemaking may be required when there is obvious evidence of decline in place, community or livelihood. It could be due to the loss of certain enablers, unsustainable use of resources, fragmentation of communities, or loss of agency over destiny and identity. In such instances, placemaking can act as a catalyst in rebuilding social relations, improving economic opportunities, reactivating systems or restoring the environment. Still, it may be difficult to identify how to intervene unless assets, liabilities, fissures and enablers in the ecosystem have been identified.

Are there common misconceptions about creative placemaking approaches?

Placemaking is about process, not product.

Who should do creative placemaking? Who are the stakeholders involved?

Placemaking is a process that evolves slowly through interaction and reciprocity between people and place; however, it can benefit tremendously from practitioners able to design creative strategies to tackle specific needs. The type of creative practitioner required may vary depending on the particular problem or need, and expertise might be drawn from the fields of technology, communication, management, conservation, arts, anthropology, design, etc.

For greater success, a placemaking project should involve the participation of various stakeholders. Resident and business communities, creative professionals and local authorities should act as key partners in the planning and reshaping of place. Local experts such as culture-bearers, elders, historians and business people are also integral to placemaking. Not only do they understand the workings of a community or place, but they also have the ability to translate the value of their own history into a tool for future development.

“Placemaking is about process, not product.”

How is placemaking done differently ground-up and top-down?

Top-down placemaking is generally conducted by urban development authorities wanting to engineer specific projects – market-led property development, for example. There is a tendency to limit local democracy and participation to favour the rapid fulfilment of an agenda. In such instances, placemaking is handled through a scientific and economic perspective, rather than a humanistic or cultural one. Although this approach is viewed as objective and reliable, the solutions tend to be generic. Art is often used as a veneer to enhance the look of a place or to create an atmosphere of cultural vitality.

Ground-up placemaking tends to avoid the ‘one model fits all’ approach, providing the opportunity for customised solutions. It tends to be inclusive and often involves local councils, community groups, business unions, grassroots organisations and creative practitioners. Ground-up placemaking efforts invest in more consultative, dialogical and participatory processes; these may be slower, but often result in community building and local citizenship. Design and creativity are also used as process rather than product.

How is placemaking done in spaces where there is no ownership of space, or in tightly regulated spaces?

Such spaces lend themselves more easily to top-down placemaking or intervention by outsiders. For participatory, ground-up placemaking, it is often necessary to collaborate with owners of a space, understanding their tight regulations and devising creative alternatives to fulfil shared goals. In the case of lack of ownership, creative programming can play a vital role in building a strong community identity and pride in a place. This is done by bringing focus to small group or individual interests that point towards common community goals and aspirations.

How can creative placemaking be carried out in a sustainable manner?

When it is powered by local agencies at the local level.

Why is cultural mapping important to creative placemaking?

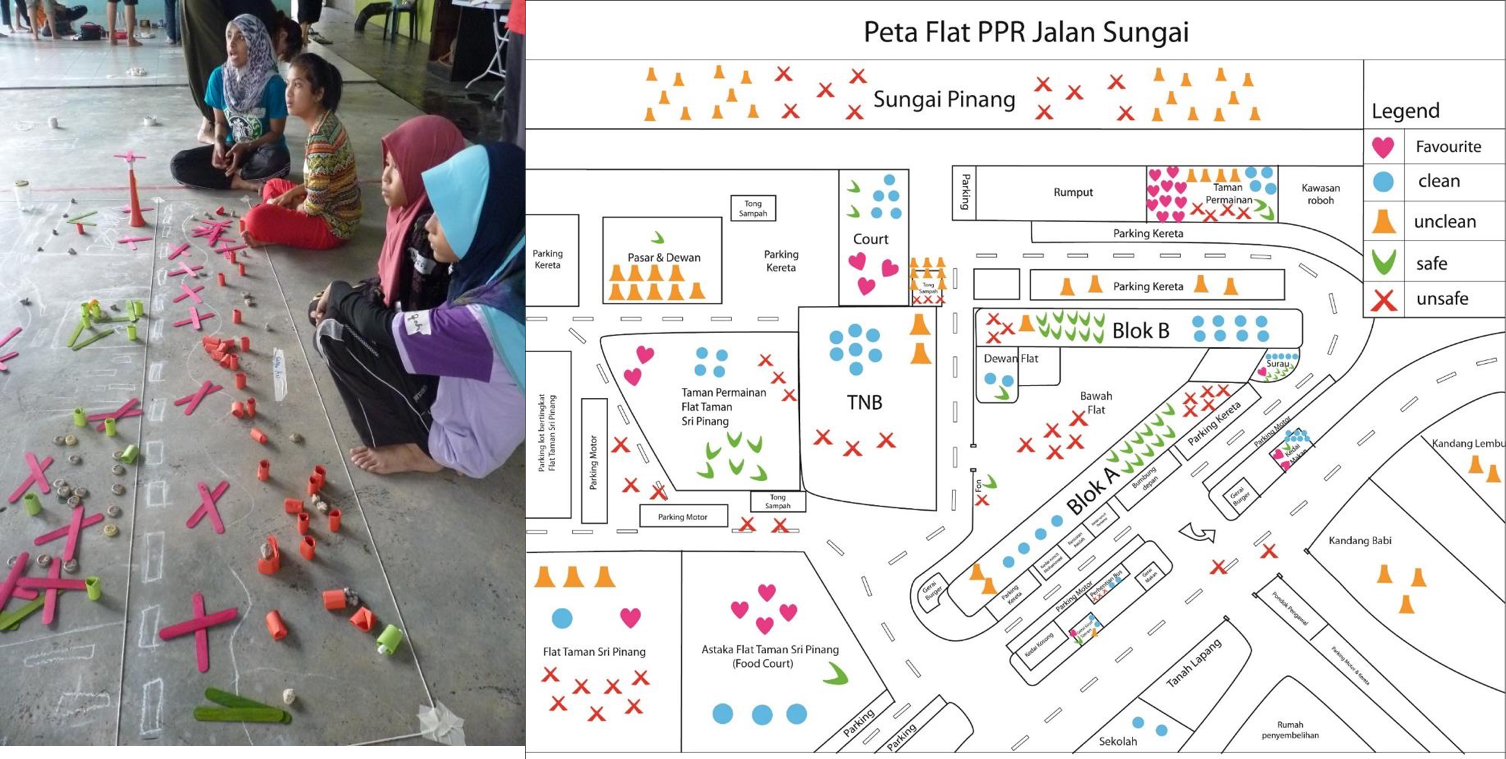

Before coming up with policies, plans or recommendations for place-related problems, there is a need to assess the site and the community’s use of space. Cultural mapping is an integrated and cross-disciplinary approach to site assessment. It provides insight into the DNA of a community, considering its cultural characteristics, ways of thinking and doing, and assets and liabilities. Cultural mapping can pinpoint missing elements responsible for a space’s decline, as well as provide information on the strengths of a place or community which can then be leveraged for regeneration. Information gathered from cultural mapping allows for more customised and culture- sensitive placemaking projects.

What is the role of the artist/creative practitioner in creative placemaking, and why is this important?

The practitioner is able to generate creative ideas or approaches, encouraging a community to imagine possible futures for their space. Artists, designers or innovators are able to get people to see possibilities for a place through visualization exercises, prototypes and small experiments testing new ideas.

The arts can be a particularly effective tool in activating the relationship between people and space. However, greater sustainability is achieved when creative practitioners are able to design community planning processes, enabling a community to translate their ideas into action themselves – with only limited external facilitation.

All images courtesy of George Town World Heritage Inc., Arts-Ed Penang & ArtsWok Collaborative

About Janet Pillai

Janet Pillai served as an associate professor at the Department of Performing Arts in University Sains Malaysia (until 2013) and founded Arts-ED (2007), a non-profit organization in Penang which provides arts and culture education for young people.

Pillai is currently an independent researcher and resource person advocating for research and development of cultural sustainability. Her specialisation is in arts education, community-engaged arts, sociology of culture and creative pedagogy. Her ground work entails research, programming and managing community-engaged projects in partnership/consultation with community, local agencies, artists and professionals.

Pillai has authored 3 books and numerous articles on arts and culture education and sustainability. She also contributes as expert resource person in organisations such as UNESCO Bangkok, APCIEU Korea, and GETTY Foundation.