Library / Field Studies

Community-Engaged Art During The Pandemic: Transforming, Transitioning, Thinking

Library / Field Studies

Community-Engaged Art During The Pandemic: Transforming, Transitioning, Thinking

Our call for artists, creatives and producers to reflect and share

In July, we put out a call requesting the perspectives of arts practitioners during this Covid-19 pandemic, to get a sense of how community-engaged art has been kept alive in this period. We asked questions such as how work has been affected and evolved, how space and digitalisation have played a role in this, and what new insights they’ve gained from this experience.

We’ve since received many varied, rich responses to our call. Twenty-four practitioners responded, and we were moved that many took the time to share at length their thoughts and experiences. We even received replies from outside of Singapore!

Some of our friends responded to the call, but the majority are practitioners whom we personally did not know before. Learning about their practice from them through this call was eye-opening, and enriched our knowledge of the field. Among the respondents are people with backgrounds in the fascinating fields of circus, heritage, and experience art, as well as film directors, arts producers, actors, designers and educators, among others. In this article, we’d like to share an overview of what we’ve learnt from them, and hopefully this may in turn help you, our dear readers, to reflect on how this period has been for you too.

For Singapore, Covid-19 brought about big shifts in our lives. A lockdown (locally called a Circuit Breaker) was enforced in early April, and lasted almost 2 months. Following that, meetings outside have been limited to 5 people, and arts venues such as theatres and cinemas have been reopened with measures requiring social distancing. This meant that many arts practitioners with live gigs have had their work disrupted, and had to adapt, either by finding new projects and alternate sources of income, or choosing to use this as a lull period of rest and reflection.

A Shift To The Virtual

In many cases, this entailed a shift to the digital, using the internet as a medium to reach out to audiences and engage communities. Theatre and performance practitioners such as Sharda Harrison, Renee Chua, Michael Cheng, Ri Chang and The Finger Players began conducting online workshops via Zoom, reaching out to general audiences. On the other hand, when it came to keeping up with communities they were already acquainted with, the more intimate means of WhatsApp was used to maintain a line of communication. Some noted that while this means of communication may feel removed to some, to others who struggle with social anxiety or shyness, it actually feels like a safer and more “immersive” space than face-to-face interaction.

Playback Theatre Responds Lebanon Show, photo provided by Michael Cheng

In other cases, WhatsApp was utilised not just as a tool of communication, but as a medium through which their artistic engagement with a community could be conducted. Ng Xi Jie (at the time of answering our call) was in the midst of carrying out a project with seven seniors. As this group was new to her, having recently returned from a residency in the US, steps were needed to acquaint herself with these seniors, and for them with one another. While shyer seniors found this means of interaction a comfortable one, others found it alienating, and it required dedicated time to recalibrate according to each individual in order to build trust.

She noted:

“Setting up a digital project space is not unlike setting up a physical one. People involved create the boundaries of the space, cultivating a microcosmic universe with its own culture and informal rules of engagement. There is a still a sense of a world (as every project is its own world), just one without the interaction of physical bodies.”

A Whaling Descendant Performs In Four Acts, a collaborative film by Ng Xi Jie made with Charlie Chace during Xi Jie’s art residency at University of Massachusetts Dartmouth in the US, photo provided by Ng Xi Jie

While the virtual and tangible do share these principles when it comes to creating spaces, in many projects, practitioners saw the need to blend the two together, creating layers of communication and connection that would make the interaction meaningful. Ellison Tan and Myra Loke, the Co-Artistic Directors of The Finger Players (TFP), created a programme involving their existing puppets’ backstories, sending these stories to the youths of their partner organisation AMKFSC Community Services Ltd. During their counselling sessions, the youths would be invited to reimagine the puppet’s origin stories. After which, TFP would produce mini short films using these retellings as the main narrative in each which later can be viewed and shared by the youths as their creations. This is a benefit that TFP noted comes with the digital, in being able to record and archive artworks.

Samsui Woman from Samsui Women – One Brick At A Time and Ah Ma from Angels in Disguise, photo provided by The Finger Players

For some groups in the community, however, the digital platform is not the best space for engagement. Instead, practitioners reach out by partnering Voluntary Welfare Organisations (VWOs) and Social Service Agencies (SSAs) or social workers who have access to these communities.

Access to the digital space becomes a challenge when many in these communities lack the technological means to create communities of their own once their physical ones have broken down due to Circuit Breaker.

Cassia Kaki 2.0, a collective that emerged from our action learning programme The Greenhouse Lab, partnered with Cassia Resettlement Team to reach out to isolated seniors, and made activity kits for them. However, explaining these kits to them was difficult as many did not know how to use technology, and could not be contacted. Thus, after the Circuit Breaker lifted, the members of Cassia Kaki 2.0 found that meeting them face-to-face to brief them was the solution. Another group of people who might be excluded from the shift to virtual space is youths from less privileged backgrounds, who often do not have access to a computer. In her work with Hopefull that engages children, Victoria Chen noted that initiatives such as the Engineering Good for their Computer Against Covid campaign are very helpful in providing them with devices. However, some find that going online would still inevitably compromise some things. Jay Che, who conducts circus workshops for youths with his team Circus In Motion, finds that participants’ engagement and precision with this very physical art form dropped when they had to hold lessons digitally.

Workshop held for students by Circus In Motion in pre-COVID times, photo provided by Jay Che

Another tension when it came to the digital was the compatibility of the artistic medium: often, a practitioner’s ability to adapt their projects with ease to online platforms depended on whether their medium was translatable online.

For Jes Sy, an arts producer who organises a community choir group, Syncroony, it was difficult to coordinate the singers’ voices during rehearsals, given that they could not sing together at the same time and in the same space. This was righted with digitalisation, in piecing together the separate parts, but no doubt, the seamlessness of in-person rehearsals was lost. Similarly, Playback Theatre practitioners Michael and Renee noted that during this period, their sessions have lost the important element of the intimacy that comes with being in the same space while sharing stories with one another, with the former noting that it has ironically become “constricted, more analogue than stereo”. On the other hand, Eileen Chong, who is a documentary film director, noted that a large part of her work does not require the element of space, in the stages of storyboarding and conceptualisation.

Care: External and Internal

The changes brought about by Covid-19 served as a signal for many of our respondents to shift their energies to caring: externally, for segments of the community who seemed to need it more, and internally, as a chance to rest and regather their energies.

Some practitioners started projects with demographics that they saw as particularly vulnerable. Among them is the aforementioned Victoria Chen, a freelance performer and educator, who started social enterprise Hopefull with a few others, in order to engage with children from disadvantaged backgrounds through activity kits which would engross them in educational ways while being away from school. Arts practitioner Jes Sy dedicated Syncroony’s heartwarming music video to workers who have been required to go to work as usual during this time: such as healthcare workers, bankers, postmen, and coffeeshop uncles, sending out the message of support and solidarity.

Syncroony’s Social Distancing Project on YouTube, photo provided by Jes Sy

When we asked what demographic respondents felt needed reaching out to the most, the majority shared that they felt the elderly are a vulnerable group. While isolated seniors in Cassia Crescent were reached out to by Cassia Kaki 2.0 and Cassia Resettlement Team, arts facilitator Soh Geok Kee (who runs a weekly Drum Circle for seniors at Kallang Community Centre) noticed that even seniors who live with family members are left alone during working hours, getting “irritated replies” by their working family members if they try to reach out to them.

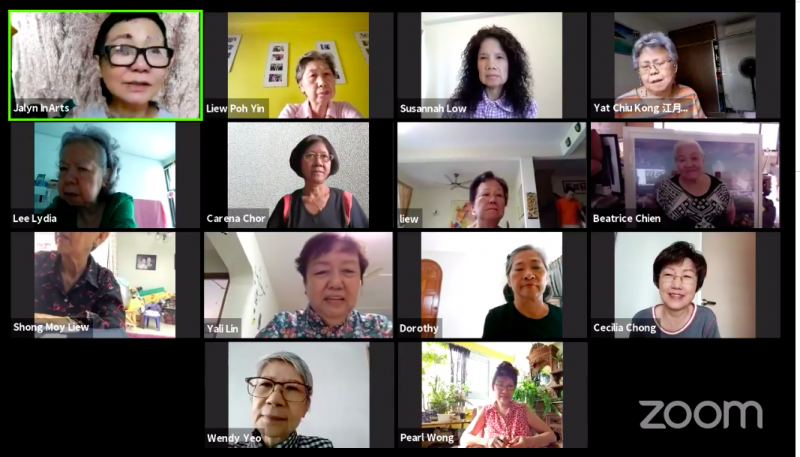

Hence, art as a tool to care for this demographic is a powerful one. Catherine Sng, who has been running the senior theatre group, The Glowers Drama Group found that during this time, her members drew a great sense of purpose and momentum from preparing a piece for The Virtual Enabling Festival by Enable Asia, which is happening on Facebook this month. This group of seniors is an extremely dynamic and adaptable one, having learnt how to deftly navigate Zoom to rehearse and showcase their work, which will spotlight the experiences of persons with dementia and their caregivers.

The Glowers’ online Zoom class, led by Jalyn Han, photo from The Glowers’ Facebook page

Very often, arts practitioners balance multiple gigs simultaneously, and this time of circuit breaker forced many to prematurely end their projects, leading to a lull period which gave them the chance to be introspective. As multidisciplinary artist anGie seah put it, embracing this alienation allowed her to enter an incubational mode in which she could rethink her practice. Similarly, Mohamad Shaifulbahri (Shai) used this time to brainstorm how his existing works could be possibly adapted to the online medium, while being open to the fact that some might resist this translation, and that this resistance could be meaningful too.

Life mOvements, a sound/movement project with seniors as part of Both Sides, Now by Drama Box and ArtsWok Collaborative in 2019, photo provided by anGie seah

Several practitioners found this time a chance to immerse within their own communities – their family members, parents, and friends.

One thing that all the practitioners shared in their responses was a renewed desire for experimentation: by exploring new avenues (such as the online world) to present their art and collaborate, and even questioning the conceptualisation of their own practices.

Eileen Chong brought up the rigidity of labels, and how labelling yourself as one type of artist may restrict your practice from evolving: during this time, she divorced herself from the idea that she is a ‘filmmaker’, and began opening herself up to different ways of arts practice. “I am Eileen, not just a filmmaker,” she reflected in a follow-up call with us. She shared that now, she sees herself as more of a creative, unrestricted by the (arbitrary) boundaries between artistic disciplines.

Eileen’s crew filming in masks at East Coast Park, photo provided by Eileen Chong

Theatre producer Jeffrey Tan has been thinking about the question of the arts as a safe space. In engaging communities through the arts, he has realised it is important to be clear with oneself and with others about why one chose arts in the first place. Having that clarity informs the way in which one may engage people through the arts, especially online, in that it leads one to inevitably exercise care, by making one’s intentions clear, and creating the right platform for trust to grow.

Indeed, intentional care can be powerful: in some instances, it transcended borders, to allow practitioners to connect with practitioners overseas who shared this same intention. A choir group based in Hong Kong saw Jes Sy’s work with Syncroony, and reached out to him for advice on how to do a similar project to honour workers in Hong Kong as well. During this time, the international Playback Theatre communities have been gathering support for the Chinese diaspora, and creating ways of fighting against Covid-19-related prejudices online.

Moving Forward

In our call, we invited arts practitioners to share any insights that have been brewing in their minds during this period, and their thoughts on the future. This resulted in many deeply philosophical insights on what art means, or may transform into, during the time of pandemic.

While many made it a point to reaffirm their belief in the arts – that it is a refuge for many to safely express themselves and react to the turbulence occurring in the world around us – experience artist Ri Chang pointed out that this time has led to a sense of loss with regard to their arts practice. With the implementation of the Circuit Breaker, many artists had no choice but to bring their work online, and this disruption happened so suddenly that it felt unnatural, and disrespectful to the authenticity of the art. Ri shared:

“We don’t give enough time mourning elements that are lost when we digitise our work. I think emotionally it’ll be easier for artists to explore digital mediums if there’s time and space given to acknowledge and grieve these losses. Because it’s not that traditional mediums are inferior, they’re merely inaccessible during this time. It’s important to honour them so we can explore and create new practices in peace.”

This sense of loss was coupled with anxiety in many answers. Is there funding available for projects to be able to transition well? Is there technology readily available to do this? Uncertainties pervade for many.

Indeed, this sense of loss is multi-layered, felt in many aspects of this ‘new normal’. The most strongly felt, perhaps, is the sense of physical absence from our fellow human beings. Every respondent touched on this in some way or other, in expressing a longing to return to what once was, to be able to be physically present with the communities they work with. This is coupled with a sense of frustration at the fact that online communication has a long way to go before it may be able to realistically and comfortingly simulate face-to-face interaction. Sharda Harrison reflects: “It’s almost as if everything has to be perfect with no technical errors in order to have as [intimate] as possible human interactions.”

Some practitioners see this shift to the digital as not temporary, but one that may irrevocably change their field’s mode of practice. As Jeffrey Tan puts it: “Online engagement is a new language that you can’t opt out from!” Arts & Heritage practitioner Fauzy Ismail predicts that Singapore’s heritage sector may shift towards using purely digital means to disseminate knowledge. This will enable local content to have international reach but this transition will take time to go smoothly since it requires the local practitioner to adopt digital means that are user-friendly, especially for elderly audiences. This sense that things may have changed forever seems to underlie many answers.

While technology may be alienating to some artists, they have taken on the mantle of breaking down the technological boundaries that keep out the most vulnerable in the community. Renee Chua expresses the need “to deconstruct our current mediums, [so that we may] marry [them] with the digital medium, to do justice to the stories and to make technology accessible.”

In our previous case study on play, leadership and communities, we’ve put forth the idea that artists and arts practitioners are able to lead the way to new horizons and ways of thinking by allowing the spirit of playfulness –the willingness to try, to collaborate, and to fail before trying again— guide their arts practice. This spirit of experimentation prevails amongst our respondents, in their efforts to find new forms of expression, communication and identity in the “new normal”, which in turn creates new opportunities, in reshaping art processes, how we relate to one another and whom we may reach.

More importantly, at the heart of this spirit is the persistent desire to remain connected to communities, whether it be familiar faces or newfound friends, a desire that is innate to all of us.

Yet the desire to connect remains. Eileen Chong reminds herself with the following questions about the need to be responsible to our fellow humans during such a vulnerable time for society:

“When I look at grants, I ask myself – what projects can I create? Is there a film I can make to help society? How many freelancers can I hire for this? What job opportunities can I provide for others while feeding myself? Are we balanced in the way we give and receive to each other? Are we still interacting with society in a healthy manner? Can I help others to digitalise?”

For those of our dear readers who are in search of meaning through art during this time, we invite you to click on the links embedded in each practitioner’s name, and find out more about their work.

Our heartfelt gratitude to all twenty-four practitioners who contributed to this piece by responding to our call! Our apologies that we were not able to feature everyone.

Project Shoutouts

We asked our contributors to share about any of their ongoing projects which they’d like to let you know about. Here are some ways in which you can experience and connect with art:

Mohamad Shaifulbahri’s next project with Bhumi Collective will be part of Esplanade’s da:ns festival. Failing the Dance: A Double Bill of Lecture-Performances premieres on 24th October, 8PM and will be available online till the 31st. Catch it online soon.

anGie seah invites people interested to participate in her art projects to email her directly at hello@angieseah.com. She has been working with communities, actively initiating participative workshops with them, for a decade. Find out more here.

Likewise, Eileen Chong invites you to collaborate, build projects, talk and contribute to her films: you may contact her via her Facebook. View her recent project Letters To God here.

About the Writer

Kirin Heng is the Communication Manager at ArtsWok Collaborative, an arts enthusiast and researcher interested in the potential of the arts to transform society. She majored in Literature, Anthropology, and Theatre and Media Studies, while going on to do a Master of Arts (Research) in Media, Art and Performance Studies.

About the Researcher

Ten Ting Yu was an intern with ArtsWok Collaborative for the past four months. She is currently a fourth-year student at Yale-NUS College, majoring in Psychology and minoring in Arts and Humanities (though there is nothing minor about the arts!). When she is not drowning in work, she can be found listening to music and admiring nature landscapes.