Library / Field Studies

Learning from the Inclusive, Community-Led Art Processes of Toride Art Project

Library / Field Studies

Learning from the Inclusive, Community-Led Art Processes of Toride Art Project

In February, before the borders began closing on the cusp of the Corona Virus (now COVID-19) epidemic, our team embarked on a well-anticipated and meticulously planned learning journey to Japan. Our purpose was to learn from Āto Purojekutō (art projects) – a local Japanese term used to refer to art-based initiatives that are composed of a “broad spectrum” of activities, involving people from different backgrounds and in different locations. 1

Of the art projects we were able to meet and learn about, the longest-running and most extensive was Toride Art Project, based in Toride, a city in Ibaraki Prefecture with a population of slightly over 100,000 people. TAP was founded in 1999 by artist and professor Mr Watanabe Yoshiaki, with other artists who taught alongside him at the Inter-Media Arts department of Tokyo University of the Arts, members of the Toride City Office and some Toride residents. For its first 10 years, TAP ran arts festivals which focused on attracting people from all over Japan to Toride to see temporary public artworks or art studios of local artists. However, after the passing of Mr. Watanabe, and the saturation of art festivals in Japan, TAP took a turn to focus inwards. This decision was also made due to Toride’s suburban character, and to cater to its diverse residents largely living in Danchi, rental apartment complexes, many of whom commute to Tokyo to work. Since then, TAP has established different art initiatives in various locations around Toride, such as the ICOINO + TAPPINO café located in the Danchi, the now defunct volunteer-run Sun Self Hotel, In My Garden murals on the Danchi blocks around the neighbourhood, the Geidai Shokudo building run by Tokyo University of the Arts and an agricultural building Takasu House (more on their current programmes below). This article is based on our visit to the city of Toride and the various TAP programmes based in its neighbourhoods, as well as a subsequent interview conducted in late April over Zoom with the Secretary General of TAP Ms. Habara Yasue and interpreted by Ms. Yachita Mio, a TAP alumni who previously interned under TAP and currently works at National Ainu Museum as an associate fellow. 2

Professor Kumakura Sumiko (left), Ms. Yachita Mio (fifth from left) and Ms. Habara Yasue (second from right), photo taken at the VIVA arts centre

We were extremely lucky to have Ms. Habara and her colleague, Mr. Akita Takao, who works for the City Office and manages art projects for Toride as well as interfacing with TAP, take us around Toride and chat with us for the majority of a day. Each of their locations around Toride was unique, as was the way in which they managed to acquire permissions to use it or work with it. For their programmes located in the Danchi apartment complexes, this was a conscious choice dating back to its beginning with its founder Watanabe, who had conducted his programmes in the Ino apartment complex, and after his death, continued as an effort to bring the project to where the people lived, and to make art part of their daily lives.

Other spaces came to them in a serendipitous way. Takasu House was an abandoned venue for farmers that the local government had suggested to TAP as a potential space for their programmes. It had so happened that a few years back, before the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake, TAP had been planning a farming project headed by an artist inspired by the writings of Naoki Shiomi, who originated the idea of “Half-farming, Half-X”, a way of sustainable communal living in which people may contribute to society by spending half their time farming, and half their time through their “natural abilities”. 3 After the earthquake hit, and Toride’s farmlands became badly affected by radiation caused by the Fukushima Daiichi disaster, the need to recuperate local agriculture arose. Together with artist Mr. Iwama Satoshi, they began to work on the decontamination of abandoned farmlands surrounding the project space at that time, and which were near the City Office, laying the foundations which would allow TAP the use of Takasu House later.

Takasu House would not have been possible without the faith and trust which the local government had accorded to TAP and its processes. From our conversation that day, we noticed the deep involvement of Mr. Akita with TAP, despite it being only one of his projects which he is responsible for in the local government. While Ms. Habara as the Secretary General knew the intricacies of TAP by heart, so did Mr. Akita, from the macro to the micro, and the policies to the names of the community members involved. Contrary to the popular caricaturing of a government official as a desk-bound bureaucrat with little knowledge of what is happening on the ground, Mr. Akita was the exact opposite: a hands-on member of the TAP community, who himself seemed to be as much emotionally invested in TAP as Ms. Habara. This is a reflection of the genuine partnership between the TAP team and the local government.

Indeed, what characterises a typical art project is its collaborative nature (drawing on local governments, universities, corporations, and civic groups). In the case of TAP, it is a collaboration between Tokyo University of the Arts, Toride City’s local government and a group of citizens who participate on a voluntary basis, and managed by its secretariat, which exists as a Non-Profit Organisation. At the heart of each programme comprising TAP is an artist and a group of citizen volunteers. Even before its directional shift inwards towards the community, a “tradition” of openness was established in TAP (in the words of Habara), in which the community members themselves have grown to become used to taking initiative and contributing ideas to new and ongoing projects. How has TAP been able to establish this, in a country whose political philosophy is Neo-Confucianist, in which a pre-established hierarchy is the bedrock of society? And how may we learn from it too, living in a society which has its taken cue from Neo-Confucianism as well? 4

This openness is a rare feat, not just for Japan, but for the realm of art in general, in which projects initiated by artists often do not have direction from anyone other than the artist. 5 Participatory art, if successful, itself goes against the Modernist Avant-Garde tradition which places the singular vision of the artist at the centre of the artwork. 6 In the case of TAP, its various programmes have displaced the artist as the centre of the piece, in favour of citizen-volunteers who are not professionally trained artists. Instead, the artists and managers of each serves as a guide, a facilitator to the “professional world” of art.

It is interesting that Habara uses the word ‘tradition’ to describe this non-hierarchical nature of TAP, providing us with an alternative tradition that we may learn from. This tradition is the legacy of Professor Kumakura Sumiko, producer of TAP, who started open meetings involving each of the collaborating organisations as well as “citizen volunteers”. In this scenario, these conversations are often facilitated by the artists and managers, giving prompts to the citizens in form of questions on what should be done next in a programme, or whether new programmes could be initiated.

The nature of these meetings is horizontal: anyone is welcome to speak up, at any time. The key is a patience to the process: many a time in each of these meetings between the managers, artist and participants, the principal artist would “sit and wait”, asking the question: “what should we do now?” There are no instances in which the artist or manager shoots down or tries to impose his or her vision on the project: each artist involved in TAP puts at the core of their practice the need to listen, value input and develop artistic ideas based on the input. As a result, the residents of Toride who are involved in the projects as volunteers have grown to have a strong sense of ownership over them.

Mr Jozuka Noboru, one of the volunteers of ICOINO + TAPPINO Café whom we met when visiting

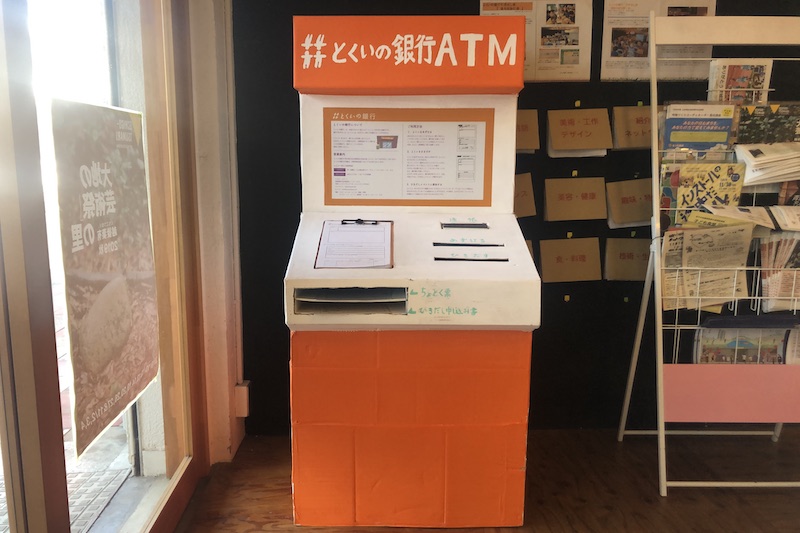

This results in a strong atmosphere of initiative and motivation. Take for instance, the case of the Tokuino Bank project in the ICOINO + TAPPINO Café, a ‘skills bank initiative’ in which anyone, but mainly residents of the Toride City neighbourhoods, can submit a piece of paper detailing their skills into a cardboard box shaped like an ATM. The idea is one in which participants may exchange skills and learn from one another, or do activities together. The initial idea of a ‘bank’ which would provide opportunities for the residents of Toride to socialise, came from artist Fukasawa Takafumi, yet the ‘bankers’, citizen volunteers who carry out the project day by day, are the ones who have taken this idea further, and thought about how to “play and have fun” with it. This dynamic is rooted in trust, from either side: the trust of the citizens, who believe that what the management and artists have at heart is the interest of the citizens, and the trust of the management and artists, who have let go of the reins and allowed the citizens themselves to create, with their assistance.

What comes to mind is Malaysian practice-led artist Chu Chu Yuan’s theory of negotiation-as-active-knowing, a form of “experiential relational responsive inquiry” in which immersive interaction and involvement within a longer period of time with otherness (in this case, the artist and management vis-à-vis the citizens) result in acts of imagination – a rethinking of the current situation, a “reorganising of ideas” and improvisation. Within this framework, artists do not see themselves and their vision as subservient to the community, but their power as “fluid and dependent on particular circumstances, contexts and constituency”. Instead, it is a constant process of active negotiation and recalibration based on the situation, through “relational knowing” formed over time in working with one another. 7

Despite the fact that the citizens are seen as the core of TAP, the artist in each programme is not easily replaceable with a community worker with some experience using art-based processes.

“It isn’t possible without artists because the purpose of intervention by artists and community workers is very different. Artists will come and join this kind of project because they want to find out something and explore something that hasn’t been done before. They want to find new values, new perceptions, basically, they are seeking for a future that nobody has imagined before. On the other hand, the community worker will aim at a better version of the current situation. They will have this clearer vision of what will be the better version or what has to be improved.”

The impulse to rethink and reimagine the status quo comes from the artist, and subsequent encouragement for the citizens to do the same. Because in the eyes of each TAP artist, process is favoured over the end-goal of an artistic object, and there is opportunity at each step of the way for people to join in and chip in with their ideas, with different levels of commitment. According to Ms. Habara, “any random idea” is taken up by the artist, to try to develop something from it.

Yet some moderation is needed, especially when the groups present in each meeting are becoming larger and larger. The management foresaw the problem of a programme group becoming so large that the risk of debate on the direction of a programme, rather than a conversation, was high, such that those who had shyer, passive personalities would not be able to speak up. In the instance of Sun Self Hotel, the project team composed of citizen volunteers was becoming so large that the management saw the need to choose a moderator out of the volunteers, who they had previously noticed had the habit of including those with weaker voices but with a “strong motivation” and commitment to the project. Subsequently, within the Sun Self Hotel project itself, there were several leaders chosen for multiple facets of the project. It could be anyone: a senior, or a high school student, who proved to possess a good listening ear and a capacity for the patience to lead.

Participants of Sun Self Hotel in front of ICOINO + TAPPINO Café, photo by Ito Yuji, © Toride Art Project

This boils down to the most fundamental philosophy of TAP: to “provide a new perception or way of looking at the world, and changing the ordinary and common way of looking at the world to something new”. What is interesting is that these new perceptions are sought from the citizens of a community themselves, with the facilitation and prompts of the artists and management team. The monocultural societies of the modern world which dismiss or hide otherness exist not because they are made up of only one type of people, but because they are a myth created by a hegemonic culture. In this monocultural dynamic, there is no room for diversity and inclusivity, for smaller voices to be heard.

TAP strives to provide a safe space in which these dominant ways of thinking may be challenged through the inclusion of everyone, and paradoxically to create new ways of thinking by consulting the people who already make up a society themselves. This would not have been possible without the artistic impulse which favours alternative ways of thinking without prioritising a set end-goal, but new ways of thinking. While this approach is not a new one, the manner in which TAP has been so successful in fostering an atmosphere of openness amongst its community members is a valuable lesson for not just socially-engaged art, but how a society might become more civic-minded through art-led processes.

[1] Kumakura, Sumiko. “An Overview of Art Projects in Japan: A Society that Co-Creates with Art.” (Tokyo: Tokyo Arts Research Lab), 3.

[2] Habara, Yasue. Personal interview interpreted by Yachita, Mio. (Conducted online, 19 April, 2020.)

[3] Shiomi, Naoki. “”Half-Farmer and Half-X” to Create Rich Relationship between Community and People.” Japan for Sustainability. (Sustainability College, January 26, 2019).

[4] Moyer, Justin Wm. “How Lee Kuan Yew made Singapore strong: Family values.” (Washington Post, March 23, 2015.)

[5] Helguera, Pablo. Socially engaged art. (New York, NY: Jorge Pinto Books, 2011.)

[6] Kester, Grant H. Conversation pieces: Community and communication in modern art. (California: Univ of California Press, 2004.)

[7] Chu, Chu-Yuan. “Negotiation-as-active-knowing: An Approach Evolved from Relational Art Practice,” in Art-led participative processes: dialogue and subjectivity within performances in the everyday. (Malaysia, Strategic Information and Research Development Centre), 173-199.

Cover photo: Participants of Sun Self Hotel. Photo by Ito Yuji, © Toride Art Project

About Toride Art Project

In the Toride Art Project (TAP), Toride residents, Toride City, and the Tokyo University of the Arts have been working together since 1999. TAP aims to develop Toride as a cultural city by supporting young artists in their practice and disseminating their work, as well as providing residents with various opportunities to interact with art.

Current Toride Art Project programming

Core project 1: Art in Danchi

A social, experimental art project organised in the Danchi, apartment complexes. Since Toride city is a dormitory town for many people who work in Tokyo, the people who live in Danchi come from different backgrounds, have different points of view and are from different age groups. TAP thus set up a sustainable art project which operates daily, in order to investigate how the local community could be changed through arts-based communication, and how relationships could be formed through art processes over time.

Under this core-project, TAP organises the project space (ICOINO + TAPPINO) and several art programmes with artists and residents.

ICOINO + TAPPINO

A café-style project jointly operated by Toride Ino Residential Neighborhood Association, the Toride District Consumer Affairs Committee, and the NPO Toride Art Project Office, in cooperation with the Toride City Elderly Welfare Division. Its aim is to increase face-to-face interactions between the residents of the community, and it is run by community volunteers, daily from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.

Tokuino Bank

Also hosted in this café, to the left of the entance, is the Tokuino Bank, by artist Fukasawa Takafumi, in which residents of the Toride City neighbourhoods are able to interact by exchanging skills or spending time doing mutual hobbies together. Each resident can submit pieces of paper detailing their skills or interests into a wooden cardboard box shaped like an ATM. The bank clerk in charge of maintaining this system is also a volunteer.

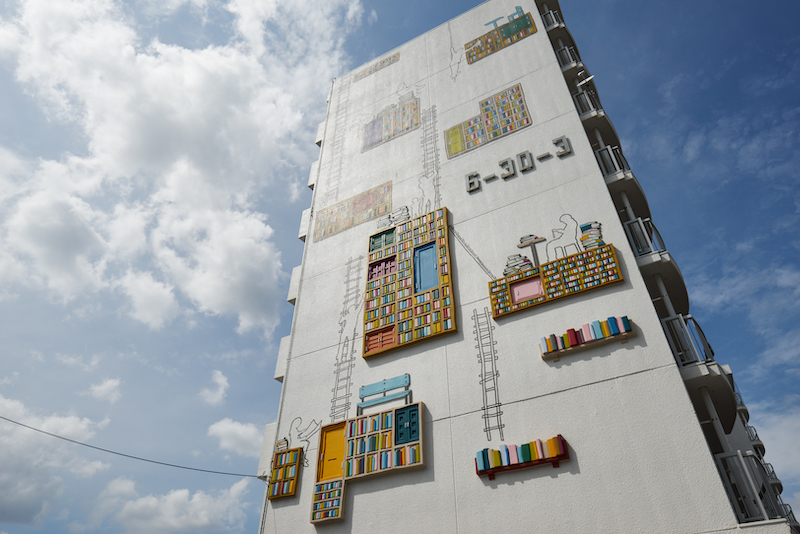

In My Garden

A project of artworks painted on the walls of about 15 blocks of the Danchi complex which features the stories of the residents, especially their daily lives. Artist Kouo Uehara chose particular stories of residents with the intent to make them feel like the estate is their garden.

Core project 2: Hanno-Hangei

The objective of this project directed by artist Iwama Satoshi is to find a way of living for the future by thinking and acting communally, on the ground and in nature. Partner artists and researchers of Hanno-Hangei contribute to this project through their artworks and expertise which are related to nature and the ‘necessities of life’ (衣食住 in Japanese). With them, participants continuously think about how to live, and how to handle living in nature, such as dealing with soil, plants, food, etc. TAP organises two spaces for this project, Takasu House and Geidai Shokudo.

Takasu House

At the Takasu House, artists in residence organise projects to plough the fields around, as well as create art using materials from nature, such as using mulberry and blueberry juice to paint paper kites. Formerly a farmhouse, the Takasu House is a building used as spaces for artist studios, and exhibitions and workshops are also conducted in the common spaces.

Once a year, an agricultural art festival is also held, for the residents in the surrounding areas. Residents would share home-based recipes with one another and 3 to 4 selected families would make food to be shared. After which, music compositions would be played based on the interpretations of the flavours of the food.

Geidai Shokudo

This building is owned by Tokyo University of the Arts, and used by TAP as an experimental art space to introduce local residents to different artists, both local and from outside of Toride, and sometimes from the university. The building includes a canteen and a gallery for art exhibitions. The ploughing project has also started here, for which local residents and young artists do yard work and cultivate the new land into a “play ground”, in which future generations who are multi-diverse, and multi-generational can play.

VIVA

A location recently acquired by TAP, VIVA is an arts centre located in a shopping mall in Tokyo. It is one of the few locations outside of Toride. Formerly a MUJI outlet, it has been converted to be a spacious arts hub with gallery-spaces, a café, study areas, and an archive for Tokyo University of the Arts student artworks. With VIVA, TAP hopes to build community, and reach out to demographics such as youth through art.

More about Toride Art Project and all its programmes/ core-projects can be found on its website in both Japanese and English.

About Habara Yasue

Born in 1981, HABARA Yasue is the Executive Director and Secretary General of Toride Art Project (TAP) Office, a non-profit corporation, which coordinates art programmes. She headed the transformation of TAP from an art festival format to having projects which operate all year-round, and currently oversees the creation and practice of art projects in the suburbs.

Her major was producing “Art Projects” in suburbia through developing socially-engaged art and community/relational art with diverse groups of people, including artists and local residents. She started her career working as an intern for the Toride Art Project (TAP) while a graduate student. She also worked as a planner for the Cultural Complex in the Shizuoka Cultural Foundation from 2007 to 2008, before returning to Toride Art Project. The works she coordinates and represents in TAP are ICOINO+TAPPINO (2011-present), Sun Self Hotel (2012-2017 with KITAZAWA Jun), and Geidai Shokudo (2017- with IWAMA Satoshi).

(Photo by: Xu Lijing)

About the writer

Kirin is the Communications Manager at ArtsWok Collaborative, an arts enthusiast and researcher interested in the potential of the arts to transform society. Born in Delft (Netherlands), she has lived in Singapore, Taiwan and Australia, and returned to the Netherlands to major in Literature, Anthropology, and Theatre and Media Studies.