Library / Field Studies

Reflections on Disability, Accessibility and the Digital in “What If”

Library / Field Studies

Reflections on Disability, Accessibility and the Digital in “What If”

The Beginning of What If

Last year, amidst planning M1 Peer Pleasure’s 2019-2020 iteration on the issue of disability in Singapore, we reached out to Okorn-Kuo Jing Hong to invite her to direct a play. This play1 would be fronted by a cast of people with disabilities in Singapore, with the aim of spotlighting their points of view, without exploiting their lived experiences for the spectacle. Initially, the title of What If arose from this desire to excavate these experiences: in Jing Hong’s words, What If stood for many open-ended questions. “What If people with a disability, are seen as not having a disability, but their disability as an opportunity, without avoiding and negating what their life has been and the challenges that they have to go through? So in that sense, their experience of having a disability creates a different perspective of expression.”

And, with Covid-19, causing our production to move online, these questions of what if grew in number.

The designers of the production played a non-traditional, much involved role from the outset. They were invited by Jing Hong to be part of the devising process, as she noticed they seemed to be a group of sensitive, proactive people, with the predisposition to be curious – and empathetic – about different points of view, informing their design. And later, during the shift to the digital, when access to the show would be more dependent on the senses of sight and sound to carry the performance to audiences via the internet, they took on the roles of co-creators. Alongside this transition from a theatre show to an online one, New Media Director Lim Shengen was brought onboard to facilitate this. In contrast to most of the team who were experienced in theatre, Shengen was an artist with a background in fine art and design.

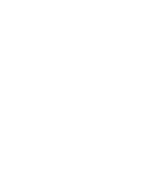

Frozen. Broken. Poof!, post-show dialogue screen capture.

Hence, this made the creative process of What If a cross-road of sorts, in which many different backgrounds, experiences and lenses played a role in shaping each piece. What If has been a collaboration between designers and artists, traditional theatre-making and New Media, people with disabilities and people without disabilities. Each step of the way, an effort was made to translate different languages and points of view to one another. This whole process of collaborating across differences was one of learning.

Through this piece2, we hope to share our experience of trying, for the first time to make an original, devised and digital production with a very diverse team, with the aim of spotlighting the perspectives of our cast who have disabilities. This piece is an amalgamation of the voices of each of us who were involved in this process, and our experiences, based on a series of interviews ArtsWok, as the festival producer, conducted with the cast, designers, production manager, and directors. We hope that these sharings of obstacles we ran into along the way, and things we learnt, might create questions, and points of consideration, for anyone in the arts and outside, hoping to do a collaboration with disability as one of the factors in mind. We do not claim expertise nor prescriptions on how to shape a production, but hope that our work with What If might provoke you into thinking further, and inspire you to start collaborating with people whom you might not have thought of connecting with before.3

What does Disability mean in What If?

As far as the producers, designers, and production and stage managers were concerned, we set out not knowing much about the nuances and specificities in the experiences of those with disabilities. In order to make an informed, responsible festival, a resource panel consisting of researchers, educators and advocates was assembled. While they were consulted from the outset, having a set of specialists on disability was not enough to inform us about working with a cast of people with disabilities, simply because each person has their own preferences, regardless of (dis)ability, and only through asking questions specific to the scenario are we able to provide an inclusive environment for both artists and audiences with disabilities.

Given that our festival’s theme was disability, specifically a youth theatre festival exploring the social issues surrounding disability, we were cognisant of the fact that we might be at risk of pigeonholing the wide array of disabilities into a few plays. Each step of the way, we sought to keep in mind our original goal of trying to spread a deeper or different awareness of disability in Singapore, in a nuanced, responsible way, and in consultation with various points of view from the community themselves.

Having the five cast members, each of whom has had a different experience with disability, was very valuable to informing the way the festival was shaped. To start from square one, we asked them what disability meant to them, to which we received a variety of answers, some of which are:

“A person with disability is someone with a different set of abilities or who focuses more on one ability, or who is heavily reliant on it, rather than having a well-balanced set of abilities. For example, for a person with a vision impairment or who is totally blind, we will tend to rely on our hearing ability more, as well as vocals, compared to movement and all that.”

“Disability just means there are things that I cannot do. Everybody has things that they can’t do. For me, I just happen to not be able to walk or use my hands properly.

To me, disability is just a label society puts on me. I basically live my life as normally as possible with my own constraints. Of course, it gets frustrating, but it only means something to you if you put emphasis on it. To me, by living my life the way I want it, without thinking so much about what society thinks of me or how society will view me because of what I choose to do, despite my disability, that’s how I advocate for myself.

I don’t like the term “special needs” because everyone is special. I believe everyone is made in his or her unique way whether you have a disability or not, and just because you’re disabled doesn’t mean you are special, you are just like an ordinary human being. I think the term special needs just brings a negative connotation. Like we are not able to care for ourselves or we are not able to support ourselves.

We are able to do things but sometimes it’s more like society who disabled us. When we are born disabled, or when we have something happen to us that makes us disabled, our bodies just adapt.There’s nothing special about being on a wheelchair or about using a text reader, or whatever. It’s just a tool that we use to continue living our lives as normally as possible. It’s more like these are things we have to use to make it more adaptable for us, because the world is not catered to us otherwise.”

lvni, who also has a vision impairment, and is cast member Wan Wai Yee’s partner in band Strawberry Story, assisted her during What If. He added:

“Disability shouldn’t segment everybody, it’s just that we all have to do it in different ways. Let’s say about going to a destination, from here to Tampines, one person can take a car, the other person can cycle, so you think the cyclist has a disability, very slow. But in the end, both still can reach there, it’s just people travel in different ways.”

Tan Beng Tian, our Assistant Director, had an interesting perspective to add:

“I believe that disability is in all of us. We have different points in our life in which we experience disability, like when we get injured, we have a fracture in the arm or we break a finger due to an accident. For that particular period of time, we experience a temporary disability. I heard this from Linda Prabhesh of Rainbow Centre:4 “we are all soon to be disabled anyway” because when we grow old, our eyesight, our ears are failing, our knees are buckling, so we are slowly moving towards disability. We are growing up, growing old and growing towards disability.”

Language is a crucial factor to consider when portraying communities. We learnt about some of the intricacies and politics of each term that is used to refer to different disabilities, especially through our marketing. Unfortunately, sometimes we did not realise this before launching content to the public, and were kindly corrected by people in our comments or through acquaintances from the disabilities community. Our Assistant Producer Charlene Haridas reflected on this:

“We experienced some backlash regarding the choice of vocabulary. For instance, I learnt that the term hearing-impaired is considered derogatory, among the deaf and hard-of-hearing community. The latter is preferred.

When we first chose to use the term “differently-abled” in our marketing communications, the intention was to flatten the power dynamics between people with and without disabilities, and foster a sense of empathy. Can we provoke the public to consider the fact that we are all disabled in some ways? For instance, are the spectacles you’re wearing a form of disability?

But a cast member brought up feedback regarding this choice of term. The baggage it carried dawned upon me, as I searched deeper into the discourse surrounding this term. Actually, the term can also be seen as a euphemism. It can potentially diminish the very real and difficult challenges persons with disability face in their daily lives. It softens the political positioning of disability, making it more palatable for people without disabilities.”

The cast, designers and creative team of What If in Tzu Chi Humanistic Youth Centre during the devising process, before Covid-19 restrictions.

Adapting to one another and the digital in What If

One vital question that Jing Hong bore in mind while devising and rehearsing What If was: How should they organise a dynamic of integrity in which the cast and Timothy (one of the designers), who had disabilities, and the production team and designers, who were so-called non-disabled, would have equal space – especially bearing in mind the bigger environment of society in which able-bodied people dominate the mainstream?

Initially, when they were in a physical rehearsal space at Tzu Chi Humanistic Youth Centre, Jing Hong set aside the time before the process of devising began to allow everyone to acquaint themselves with the space, and find their own ‘corner’ in which they could feel comfortable during lull periods. For the two performers who are blind, Hidayat and Wai Yee, the spaces were described in detail, and volunteers who had been brought onboard for the rehearsals were on hand to help them navigate only when the former would not be able to by themselves using their senses of sound and touch.

Another layer of vulnerability for the cast was the fact that they would have to perform in front of the whole team during the devising process. Jing Hong realised that this would be intimidating, given the double vulnerability of performing something they each created. Thus, she decided to make the rest of the team create and present a piece of work so that they would have a hands-on experience of the technical and psycho-emotional journey of creating and presenting a performance. This was an equalising tool which allowed the non-cast members to empathise with the intimacy of using one’s own body as a medium for art.

And another question: What would theatre mean once its physical stage was dissolved into an online production, given that the integrity of theatre is traditionally rooted in physical space?

Volunteer Zul with Hidayat during a What If devising process rehearsal at Tzu Chi Humanistic Youth Centre.

When the production migrated to Zoom, everything became 2D, and everything you saw of the person and their space was partial. This meant sighted people had even more of an advantage than normal, as people who have vision impairment would have only one sensory apparatus left (sound) to rely on. Now, more than ever, the team would have to make the effort to proactively communicate with one another and synchronise.

Clarisse Ng, our Production Manager, was confronted with this big shift: many questions arose as the role of Production Manager was completely transformed.

“A lot of interesting and eye-opening discoveries were made for me: like if you’re blind and on a video call, you can’t see everybody’s space, but everybody can see your space.

Which prompted the question of whether, as a production crew, do you go to someone’s house? Are people okay with our crew coming over?

And I think from a production point of view, the issue that we need to make the shows accessible for audiences, either through pre-show audio description sessions or Zoom orientation sessions. What does it mean if you are blind and how do you log into Zoom? And then of course the captioning for the show was a whole other thing. It’s many layers to take into consideration.”

Frozen. Broken. Poof! Left: Wan Wai Yee, right: Tung Ka Wai. Screen capture from show.

Ka Wai shared5 as a long-time theatre practitioner himself, this unprecedented situation of using his room at home as a stage gave him new ideas to contemplate:

“I would never have imagined using part of my room as the so-called stage, and using a camera to so-called stage the space. It really made me re-look the space I use to sleep in, to live in, that it can also allow for a lot of different possibilities.

If we are doing a piece of work online, how can it bring a new perspective to the content and not copy and paste it to an online version? We would still have loved to have a physical space and actual performance in a studio or Drama Centre. But for online, there are new possibilities to how far it can go or what sort of material or content can be developed, and how it should be developed.”

Yet a difficult period for our cast member Stephanie, who has cerebral palsy and uses a wheelchair, was the Circuit Breaker, during which access workers6 were not considered Essential Workers.7 Without her access worker, Stephanie was unable to participate in warm-ups with the rest of the cast, and had difficulty recording her own voice for her poetry for one of the devised pieces while reading it on the same device. For outsiders who may think that going online may be of benefit to people who have disabilities with access needs, Stephanie does not concur. For herself, she preferred to be able to demarcate work and home as an artist, and to be able to travel to the rehearsal space (with the help of an access worker).

Stephanie Esther Fam performing with her access worker Yi Wei, during devising process at Tzu Chi Humanistic Youth Centre.

Meanwhile, Shawn’s family stepped in to help him with rehearsals. While we had hired access workers for Stephanie, and put out volunteer calls to assist Wai Yee and Hidayat, we had not made arrangements for Shawn to have an access worker. As someone with an intellectual but not physical disability, it had not occurred to us that he might need one. However, an indirect way of trying to make the rehearsals more accessible to him was done, through frequent check-ins to ensure that he was on the same page as the rest, much like doing audio description on Zoom for Hidayat and Wai Yee during rehearsals.

This brings us to our next section: that accessibility is not a one-size-fits-all, and the key to it is communication.

Communicating towards Accessibility in What If

Accessibility in the arts has two objectives: making it possible for artists with disability to make their art, and for audiences with disabilities to access art. Both are still in their growing stages in Singapore. Clarisse shared that this is still in its nascent stages for the theatre scene in Singapore. While we had planned for and budgeted for actors with disabilities from the very beginning, we asked Clarisse what they would have done differently, and they shared:

“If we had to redo this whole experience again, what I would have recommended for the festival as a whole was to have one person on staff who was just looking at accessibility needs. In What If, within our team, we didn’t know enough, and we were all busy with something else. Instead, it was a lot of learning along the way. At least now we all know how to caption on YouTube, among other things.”

Beng Tian was asked to be our Assistant Director largely owing to the fact that she has background knowledge on accessibility, such as in directing Not In My Lifetime?. However, she had other responsibilities to handle besides accessibility needs.

During our interviews with the cast however, a recurring point was that no one can be an expert on accessibility. Instead, it can often be highly personal. Stephanie pointed out to us that the word accessibility is a paradox – while it strives for all-inclusiveness, in conflating this striving into one word, it makes it “linear”, and does not seem to take into account the plurality of the experiences of disabilities. Therefore, she stresses on the need to never assume when it comes to accessibility, and always ask the person in question whether something is working, and how else it could be done to make it easier for them to make their art, or experience the art, especially if the person is too shy or too afraid to speak up. “If you don’t ask, you won’t know. Different people have different access needs.”

It is important to not allow our fear of offending someone hold us back from asking the difficult questions, as long as they are asked from a place of sincerity. Through asking them, we provide space for indispensable conversations to be had.

Indeed, access preferences were varying for each of our cast members. Shawn revealed the key to his own lingo is breaking instructions into step-by-step, perhaps not needing an access worker so long as someone takes the time for this. For instance, in her voice training with him, Beng Tian read each line out to him when recording for the What If Aliens animated shorts.

What If Aliens: Planet Ambyond. Screen capture from show.

Even the same person may have different access needs over time. Wai Yee pointed out:

“For me accessibility must change on a daily, monthly basis. As I move on and learn more things, I think I’m able to access it better. Maybe some blind people feel “I’m blind full stop, that’s all I can do, that’s all I can think, that’s all I can learn, or that’s all that’s accessible”, but it’s not true for me. I suppose it’s different for everyone. It’s a lot about my learning along the way, learning about life.”

Wan Wai Yee in Frozen. Broken. Poof! Screen capture from show.

Due to the Circuit Breaker, Wai Yee had to learn how to film herself for Frozen. Broken. Poof! , and take into account things such as camera angles and lighting, despite not having considered it before as someone who is blind.

A curiosity to learn more about people and stand in their shoes is extremely useful in striving for accessibility. Beng Tian, who is an independent theatre practitioner, began her interest in accessibility in theatre after she became friends with people from the vision-impaired community a while back. She stressed the importance of this first step towards accessibility, in not just remaining acquainted with, but truly getting to know people who have disabilities; such that you begin considering them in your everyday, and letting curiosity of how they may perceive your work, or how they might not be able to, guide how you shape it.

Another way of approaching accessibility is by seeing it as not merely in relation to disability, but a mode of creativity. Lim Shengen’s role of New Media of Director was created to adapt to the changes of going digital, and help bring What If online. He shared:

“If we were to provide content for disabled viewers and users, it’s dependent on how creative we are. It doesn’t mean that accessibility makes us more creative, but we have to be creative to provide for the accessibility.

The word ‘design’ literally means to solve problems. Thus, is this really called accessibility, or can we call it disability design? That would be really interesting to look at it theoretically for designers. I guess for artists, it is also the same thing. In my most humble opinion, I don’t see a difference between design and art. The line is very fine, both seek to solve problems and both seek to try to reach out to audiences as much as possible, no matter whether they are disabled or not disabled.”

Stephanie stressed on this principle that artists should adopt to reach out to all sorts of audiences too:

“I just hope that when artists think of making art, that they will always think that there are people with certain needs to be met in order to enable them to enjoy art, with captioning, audio description in their art. Because if your art piece is not accessible, it does not mean that people with disabilities don’t want to see it, or that they don’t want to come to your art installation. It’s your loss that they don’t, because for me, every disabled community member has their own input to give as an audience. And if you don’t allow them that, then you are side-lining one whole group of audiences that have a wider range of opinions than you could ever fathom.”

Accessibility is intricately tied to how we live everyday life, in things that we may normally take for granted. For instance, we found that ticketing platforms like SISTIC are not accessible to people who are vision-impaired, and soon realised neither is internet banking. Charlene shared:

“When the time came for us to launch ticket sales for What If, we assigned our colleague Ting Yu, as the ticketing agent solely for bookings from the blind and vision-impaired community, who could email or message her at their convenience. It didn’t end there. We realised iBanking was not accessible to all from this community, so we prepared a step-by-step guide for those who needed it. However, there were patrons with OCBC bank accounts instead of DBS, and our guide did not apply to the OCBC iBanking interface. As a last resort, we would ask the blind patron to seek help from a sighted friend to help them make payment via iBanking. I don’t really like the last option, as it denies a person their sense of independence, when they have to seek additional assistance for a common daily task.”

A Space for Artists with Disabilities to Grow

The field of disability arts – art by disabled artists about their experiences of disability – is growing in Singapore. However, to a practising artist who happens to have a disability, sometimes the term “disabled artist” is thrust upon them without their choice, and their art is perceived to be defined by their disability.

Stephanie shared about this dilemma: To say that I need those labels would not be true. If someone were to physically see me, they obviously know that I’m already disabled. But I do it because you have to survive in this society and you have to state your place in a society that doesn’t otherwise see you if you don’t. To me, I’m an artist first before anything.

Stephanie in Stained. Screen capture from show.

In a similar vein to poverty porn8, the trope of involving people with disabilities achieving a feat – inspiration porn – is often used in mainstream media to garner the reaction of awe. Yet this awe is symptomatic of an infantilising disbelief that people with disabilities are capable of such feats, a damaging prejudice that can be a barrier for artists with disabilities trying to break into the industry and be seen as legitimate artists. During her interview with us, Wai Yee related to us her experience of being at a show in which one of her friends who was blind was performing his comedy show. They had all been enjoying it until one of the organisers remarked: “Wah, I forgot that he’s blind”.

Wai Yee continued: I’m quite tired of people who say “oh you are blind, you do triathlon, oh you sing, you are so inspiring!” I mean don’t give me that nonsense, I’m just a normal person who tries to live my life, we are all the same. Don’t put me on a pedestal, I’m not a god.

Hidayat told us that he discovered his talent of using funny voices to represent different characters after becoming blind, a skill which was used during What If Aliens, in which he played a few characters in Shawn’s imaginary world. Yet he was quick to add that his enhanced sense of sound is by no means a super power, and he does not want to be seen for his disability. This sentiment was conveyed in how Fetching Sanctuary referenced a Facebook post by an American nurse, titled Do Not Call Me a Hero. Indeed, the distinction Hidayat makes is important: that people with disabilities have no choice but to be reliant on a particular ability, and this is why it is more enhanced in them.

Alien Mee voiced by Hidayat, in What If Aliens. Mee is the leader of the alien species living on Planet Ambyond. He is big and burly. He receives intergalactic messages via the three antennae at the top of his head.

Similarly, upon being asked his thoughts on what disability means, our cast member Shawn, who has Down Syndrome, replied that he does not define himself as someone who has a disability: People with disabilities are people in need, special needs. They are special needs but they are not me.

The term “special needs” over time has objectified children who need special education by becoming itself a noun or adjective in people referring to such children as “special needs”, minimising them to their disability and not their identities as people. In his refusal of this term, Shawn indicated his wish to not be defined by what society has labelled him as.

Ka Wai had a humorous way of expressing this. When asked “how would you like to be mentioned as an artist?”, his reply was: I want to be called handsome!

By normalising the presence of artists with disabilities on mainstream platforms, in which they are free to make whatever art they want, without it being defined by or related to their disability by audiences, misconceptions such as the ones aforementioned can be overcome.

Wai Yee and Ivni expressed their desire for more opportunities to grow and be celebrated for their artistry:

“Bringing the disabled people, taking them and training them and helping them to make it into a high art is very new even to Singaporeans who are used to seeing charity shows: “oh, sing, I pity you, so I give you some money!

We want more than that. We want to be deserving of whatever we get and we want to get more. So to be able to get more, we have to train. We want the same opportunities as everyone. We want to bring arts to a higher place for the disabled people. So that people won’t say “oh you are disabled so you are good”, but instead, “you are good but you just happen to be blind”.”

Meeting Halfway

This was M1 Peer Pleasure Youth Theatre Festival’s last year, owing to our titular sponsor pulling out. We operated with the philosophy of co-creating work that is original, in order to bridge across difference. When there is enough time, space and resources to co-create something that is original, you are able to explore the depth of an experience, and draw out stories specific to it, to ultimately communicate it with audiences. And along the way, synapses of understanding and empathy are formed through connecting over co-creation.

Moes, Oliver and Timothy are students from Nanyang Polytechnic, who came onboard as designers for What If as part of their Final Year Projects for school. Initially, their role had been as set and visual designers. Yet along the way, their role evolved to that of co-creators, each being involved to different extents in the four shows of What If, especially since a digital production might not necessitate a set in the traditional sense of theatre. Moes was the visual designer of Frozen. Broken. Poof!, assisted in the running of operations for all four shows, and also served as a videographer alongside Oliver for Stained. Timothy had a special role in 0 dB: it was based on his own experiences of being “profoundly deaf” and discovering cochlear implants as a child.

Tung Ka Wai and Timothy Hua during 0 dB. Screen capture from show.

Their lecturer Ong Guat Teng, who served as their mentor on this project, shared that she has noticed their growth as empathetic, receptive and experimental designers through this process. For Moes and Oliver, their work with Stephanie played a big role, moving them and inspiring them to create a visual track to her poetry. And for the three of them, this experience helped them to shape their ideals for the future of an accessible arts scene in Singapore, one that they have the potential to shape.

This piece ends with a question: how may we, as audiences, create a desire and movement for more art which is driven by artists with disabilities? How may we, through our demand, create an industry that is open and conducive to their work? For it cannot always be people with disabilities advocating for themselves.

We would like to shoutout projects and arts organisations which have sought to spotlight artists who have disabilities: Unseen, the Inclusive Young Company (sign up here) by Singapore Repertory Theatre (SRT), VSA(S) Out Loud, as well as Access Path Productions.

There are also training programmes available for anyone who wishes to learn more about accessibility in the arts: SRT’s Disability in the Arts Disadvantage in the Arts and Access Path’s Disability Awareness Training Through the Arts.

For anyone seeking to do a production involving people with disabilities in Singapore, we have some non-prescriptive suggestions of some insights we learnt along the way, distilled from the interviews conducted with our team:

Things to think about when working with artists with disabilities

Compiled by Clara Lim

Preparing for the production

- Research

- Gain general knowledge about disability/disabilities

- Interact with members of the disabled community to understand the diversity and intricacy of experiences more through their first-hand accounts

During the production

- Communication

- Minimize assumptions

- Consider individualized (access) needs e.g. hiring access workers, providing audio description

- Understand what are preferred vocabularies/terminologies to be used

- Production Planning

- Decide on the degree of accessibility integration early on (eg. if an accessibility consultant needs to be hired)

- Marketing

- Attempt different approaches that cater to specific cognitive and sensory needs e .g. jingle advertisements for people in the vision-impaired community

- Plan for how audiences with disabilities are to indicate interest in attending your show e.g. purchasing a ticket, registering on a particular platform etc.

- Accessibility as Art-making

- Working with artists and creatives with disabilities allows for experimentation with accessibility in the art-making process, enabling different artistic expressions

- Accessibility for Audiences

- Consult the community who will be experiencing your work and get feedback e.g. through open rehearsals

Throughout

- Be courageous: whether in asking for inputs/feedback or in exploring novel methods

- Don’t be afraid to offend or ask difficult or “stupid” questions as long as they come from a place of sincerity