Library / Field Studies

Fostering Cultural Competence through the Arts

Library / Field Studies

Fostering Cultural Competence through the Arts

By Regina De Rozario

10 April 2023

Given the greater push for arts practitioners to develop artistic projects in community spaces, it is timely to consider the capabilities that are needed to engage with this type of work. In this field study, guest contributor Regina De Rozario reflects on the notion of ‘cultural competence’ through the lens of artistic practice, and how it may be fostered through arts-based community work.

The need for cultural competence in a complex and fragmented world

Without doubt, we are living in an age of accelerated technological innovation that has brought about an array of conflicting outcomes. Advancements in global connectivity enable us to communicate with each other with immediacy, but have also led to the formation of multiple ‘digital divides’.1 As an everyday user, I note the Internet’s growing number of tools and platforms and the paradoxes created therein. On the one hand, individuals may find community support or participate in ‘free and open discourse’ about any subject imaginable. On the other, this has not always translated to a sense of equal access, cohesiveness or enlightenment. Lines drawn between generational attitudes, political views and cultural beliefs are made more visible. At the same time, these divisions are exacerbated by narratives that seem to pit one against another. It is also apparent that certain algorithms tend to favour the circulation of spectacle, emotional triggers, as well as reductive and de-contextualised information. This noise makes it challenging for one to truly understand a given situation or each other in an in-depth manner.

In this increasingly fragmented world where ideas and behaviours formulated in online ‘communities’ become pervasive in ‘real’ spaces, it has become important to find ways in which we can communicate with more nuance, attentiveness, and care. A large part of this communicative work is to create suitable spaces for sustained listening and conversing; only then might we be able to uncover and attend to diverse points of view. It is within this context that cultural competence might be a useful concept, to frame the way we ‘make space’ to learn about each other.

Both Sides, Now (BSN) is an arts-based initiative that engages communities on the importance of having conversations about living and dying with dignity. At its core are dialogic activities, such as post-performance reflection sessions, where facilitators prompt audience members to share their thoughts on the themes featured in the showcase. Photo by Zinkie Aw.

The notion of cultural competence – sometimes referred to as ‘intercultural competence’ – refers to a set of “congruent behaviours, attitudes and policies that come together… to enable effective work in cross-cultural situations.”2 The term ‘culture’ here is in respect to the practices of a given social group, while ‘competence’ denotes the ability to function productively. The list of desired behaviours and mindsets that count as cultural competence may vary with contexts, although they tend to broadly include a keen self-awareness, observational and listening skills, and the ability to articulate similarities and differences. Cultural competence also calls for a willingness to dispense with assumptions and biases, and the humility to learn from multiple or even discomfiting perspectives.3 In sum, it is about the knowledge and ability to understand and communicate one’s own position, and the propensity and empathy to recognise and value someone else’s.

While its theoretical applications were first conceptualised in the 1980s,4 the idea of such a capability is not new. From the pre-modern to post-World War II era, ambassadors and emissaries were already seen as exemplars – figures of authority bearing the necessary social skills and intercultural insights to negotiate for shared political or profitable outcomes.5 By the 1970s and 80s, an expansion of international trade and migratory movements brought upon a second wave of globalisation.6 With it, the need for business leaders to develop their own frameworks; foregrounding a kind of persuasiveness, savvy and adaptability that would help them form strategic partnerships within the global marketplace.

Given that the waves of globalisation have not subsided, but have in fact intensified due to heightened connectivity, migration and displacement, we can anticipate more demographic shifts and cultural transformations. Cities that adopt a more open, welcoming and cosmopolitan outlook will be further animated with an array of languages, beliefs, and customs changing the shape of their everyday environments. Beyond the work of trade and political diplomacy, a consciousness around intercultural engagement has also become largely present in healthcare, education, social work and other human service sectors. In response to this, organisations began to establish ‘diversity and inclusion’ policies and programmes to manage their increasingly multicultural workplace environments, as well as to attend to a wider demographic of individuals in need of their services.

Complicating this further is the growing recognition that ‘diversities’ are not limited to pronounced differences such as nationality, race, ethnicity, and religious beliefs. One’s values and priorities may also be guided by other ‘less visible’ or unspoken dimensions of one’s identity and background – such as sexual orientation, physical and cognitive abilities, or socio-economic class.7 Communities and other categorical groups are also neither monolithic nor homogeneous. They comprise individuals with specific needs or who face systemic or cultural barriers, even though they might have goals in common. All of this requires time and effort to uncover, examine and clarify through unbiased facilitation. While there are several frameworks for how cultural competence may be developed and applied, it is crucial to note that acquiring such competence is an ongoing experiential learning process as cultural practices themselves are “fluid and diverse, even within one’s own culture”.8

In spite of its challenges, a culturally competent approach applied consistently over time has been noted to reduce feelings of disparity and foster a sense of psychological safety, trust and belonging.9 It follows then that a similar approach could be considered for other fields vested in the building of healthy and holistic ties between individuals and communities.

BSN volunteers go through a rigorous experiential programme as part of their training. Beyond briefings that impart BSN’s purpose, history and programming objectives, volunteers participate in theatre games that enable them to recognise each other’s motivations for getting involved and perspectives on end-of-life. These help them to cohere as a group as well as prepare to engage with community participants and the public about end-of-life matters.

Artistic practice as a means of ‘making space’ for diverse views

Although the notion of cultural competence may not always come up specifically during discussions of artistic practice, experienced practitioners might already be aware of its place and value. As a visual artist and educator, I would argue that a primary drive for an artist (and I use this term to refer to all who engage in creative practice for work) is to closely observe the world and express a novel perspective of it. From a point of learning, art is more than a mirror; it provides a prismatic view. It can conjure new and imaginative ways of seeing and thinking about our lived experiences; and compel us to ‘step outside’ of ourselves and our patterns of thought and behaviour.

To engage in this kind of work would require artists to be deeply attentive and reflective; constantly aware of their own assumptions about what they are observing. They need to be skilled in choosing the most appropriate methods and materials to communicate their vision. Furthermore, art is most resonant when it is not prescriptive but left open to contemplation and interpretation. It is enriched through discussion and critique. In this vein, artists might – through their training and experience – already possess some of the dispositions and capabilities that could count as cultural competence, even if they might not intentionally exercise it or share the same theoretical language for it.

Apart from acknowledging how artistic practice can aid the individual practitioner’s development, one can also examine the intersection between the arts and cultural competence through arts-based community work. By this I mean certain forms of artistic work that provide an opportunity for artists to co-create with others. In particular, with individuals or groups who may not necessarily consider themselves as ‘artists’ or even see themselves as a part of an ‘arts audience’.

These artistic endeavours may be referred to by a range of labels and terms10 such as ‘community arts’, ‘arts-based community development’, ‘social practice’, ‘socially-engaged art’, ‘art for civic engagement’, or ‘art for the public’. These labels and terms are, at times, used interchangeably by the parties involved in such work even though the devised activities themselves may have varying characteristics. For instance, the artistic experience may be in different formats – such as a group performance, neighbourhood walks, mural painting, collage making, or collecting materials for a communal display. There may be different durations, modes of civic participation and contribution, and methods of curation and facilitation. What these activities have in common are the means for participants to gather, interact, and share their perspectives – firstly, about the art or artistic process they are encountering, and scaffolding upon this to talk about other experiences and concerns prompted by this shared encounter.

For Kembali, dance performance company P7:1SMA held 12 weekly engagement sessions with a group of community elders from Montfort Care – GoodLife! Bedok (top photo). Through body movement exercises and conversation circles, the elders were invited to speak on the themes of loss, belief, regret and forgiveness. These stories were then embodied in the choreography of the eventual performance staged in 2022, which was jointly performed by the community elders and P7:1SMA. Photos by Zinkie Aw.

In the last two decades, these community arts initiatives have been steadily supported by the National Arts Council and other government agencies11 as a way to bring diverse groups together, to address social concerns and to strengthen ties between people and place.12 The depth of engagement and transformation that these activities might yield, however, would depend largely on the characteristics mentioned above. Other important factors include the skills of the artists involved in designing and facilitating each artistic encounter, the level of trust and confidence present in the process, as well as the resources that are afforded.

For mid to longer term projects that run for half a year or longer, artists would be able to embed themselves in a given site and familiarise themselves with the environment and its ‘culture’. Here, the artists’ competence goes beyond reading about a site or community’s history; it involves knowing it tacitly in an embodied way. Artists may immerse themselves in multi-sensory exploration to learn not only the spoken vernacular, but also to record an environment’s visual language, sounds, textures, and smells. The research and development process would also entail spending time with the communities that would be involved in the project, and engaging them in discussions about the outcomes they seek, and what roles they might want to play in the process. The role of the artistic project here would be to provide an accessible entry point for further dialogue around how community members might relate to a particular place, to each other, and the challenges they might be facing. In turn, the responsibility of artists would be to attune themselves to the ground and assess how their intervention could bring about new connections and deeper understanding.

While it is rational to conclude that longer-term projects would have the most impact, those that run for a brief duration or have a smaller number of participants might still yield meaningful outcomes. For example, a neighbourhood composed of many diverse groups might begin with a one-day or weekend event that can improve intergroup awareness of each others’ strengths and challenges. Or, a small-scale workshop targeted at a less visible minority might reveal ‘new’ contextual knowledge about a place or an issue from their perspective. Such an endeavour would require just as much careful planning and execution to ensure participants are equally respected and welcomed, and that those on the margins are not tokenised. Artists need to be aware of their own potential blindspots, and avoid using participants to fulfil certain ‘inclusion’ agendas, or have them ‘represent’ assumed points of view.

One strategy would be to design every activity as if it were a crucial step within a larger trust-building exercise. A limited time span and scope might also help to sharpen a project’s objectives, priorities and evaluation methods. Measures of success may skew towards visible ‘vibrancy’, visitorship and participation numbers, increase in space use, and other quantitative indicators.13 That said, artists are well-placed to question and articulate how their artistic interventions produce space – in terms of the capacity and room that is needed for deeper dialogue and learning. In other words, to propose other culturally competent approaches to assessing levels of impact, resonance and transformation.

Lessons from the field: Reflections from Both Sides, Now

As iterated in the sections above, cultural competence can be a useful frame for artists who wish to focus on the space making and engagement aspects of their community projects. It would enable them to clarify their priorities; how groups should be involved; which artistic intervention would be most appropriate; what funding and resources would be needed; and how to assess impact.

Quality conversations and meaningful engagement require patience and intentional practice. It goes beyond being ‘sensitive’, ‘tolerant’ or ‘appreciative’ of the differences that others might bring to a discussion. It is also not about being passively compromising. Instead, it involves taking a critical position – actively examining one’s own inferences and expectations, cultivating a healthy openness towards uncertainty, the courage to review systems that are harmful, and arriving at a shared understanding with others.

Given the range of capabilities that are needed, it is unlikely for a single individual to be proficient in everything, regardless of their training and experience. Similarly, the work of ensuring cultural competence cannot be ‘assigned’ to just one person, nor exercised only at the point of engaging with community participants. Rather, it is an approach that needs to be imbued throughout the project’s processes, and fostered collectively with other partners involved in the work.

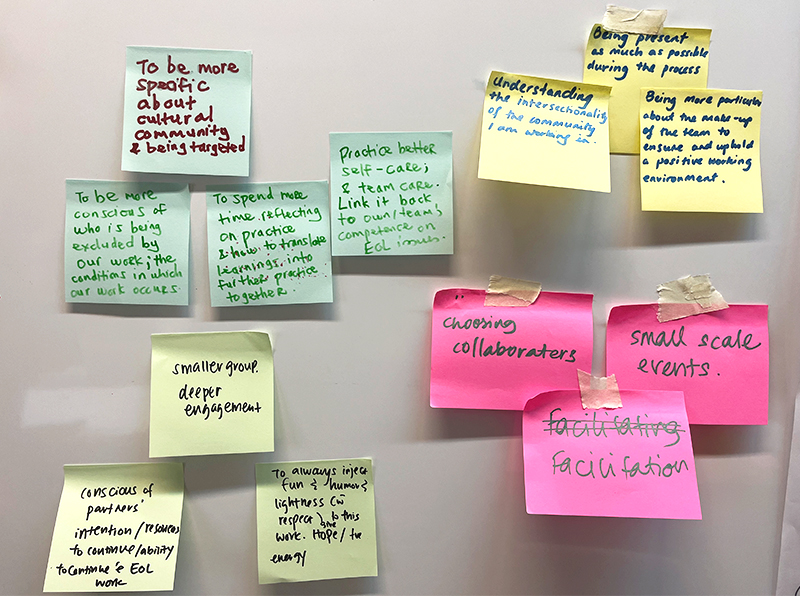

The BSN creative team gathered in January 2023 to reflect on and assess the extent to which they demonstrated cultural competence as a group (top photo). They also discussed other knowledge, skills and behaviours that would benefit the work. This included wanting to be more conscious of the diversities within communities, scaling programmes for deeper engagement, clarifying partners’ values and motivations, and making time for collective reflection and learning.

A consciousness around the need for clear and critical positioning can be found in Both Sides, Now (BSN), an arts-based initiative that seeks to engage communities on the importance of having conversations about living and dying with dignity. Produced jointly by ArtsWok Collaborative and Drama Box between 2013 and 2022, it is one of the few enduring arts-based engagement projects targeted at a wider public that is focused on a single issue. Over its ten-year span, its programming has included puppetry, music and dance performances, as well as visual arts workshops and installations that are customised for a particular site or community. A key fixture over the years is its forum theatre event, which invites audience members to intervene and respond to the dramatic narrative unfolding before them. The experience is deftly facilitated but never prescriptive nor didactic. Conflicting viewpoints may be shared and discussed; questions are welcomed, without judgement or embarrassment.

Forum theatre is a form of socially-engaged theatre that allows audiences to respond directly to a specific ‘dilemma’ within the play. In Sukar (Melepaskan), audience members were invited to help the protagonists in settling the affairs of a loved one who had passed away. Photo by Zinkie Aw.

Apart from building awareness about Advance Care Planning, estate planning and other resources, BSN has consistently created – through its use of accessible artistic formats and its invitational tone, a much needed ‘safe space’. Here, matters of death and grief that some may deem too morbid, taboo, or emotionally rife can be figured out, together. Just as importantly, the project continues to provide the opportunity for a cross-section of people across age groups, ethnicities, educational levels, and other dimensions of difference to encounter each other’s deeply-held beliefs. Furthermore, the project has also yielded a pedagogical outcome. In 2018, the team produced a toolkit on using arts-based approaches to facilitate end-of-life conversations, aimed at helping care staff and other volunteers interested in this work.

In 2020, the BSN team conceptualised a two-year edition that would focus on end-of-life conversations with the Malay-Muslim community in Singapore. The initial thinking was shaped by questions the BSN team had received in the preceding years about community-specific programming. They had also gathered from members of the Malay-Muslim community that there was interest in examining end-of-life concerns from their community’s perspective. To help the creative team with their preparation, BSN invited a group of researchers to observe a series of community engagement workshops. Here, 47 Malay-Muslim participants were asked – through arts-based facilitation – to share their views about end-of-life matters, as well as adjacent topics such as their family dynamics, commitments and beliefs. From this, the researchers produced an extensive report that provided contextual descriptions of possible ‘archetypes’ that may be found within the community, and that “reflect particular social structures and cultural norms that individuals and families are embedded in.”14

In 2021, a series of community engagement workshops were organised and facilitated by the BSN team for Malay-Muslims to share their understanding of end-of-life issues. Participants were invited to speak about their lived experiences as caregivers and how their beliefs, family relationships and community dynamics have shaped their perspectives about end-of-life. Apart from group discussions, the participants were also guided through storytelling and symbol-association activities.

From these contextual descriptions, the creative team was able to consider the possible opportunities for engagement, as well as anticipate potential barriers – in order to develop appropriate arts-based strategies for their design and programming. For example, the team was conscious not to rely on conventional cultural tropes. Instead, a critical and nuanced approach was taken for the overall visual language, keeping it recognisable and meaningful for the intended participants as well as open for a wider audience. In a way, signalling that the event was not simplistically about or only for the Malay-Muslim community, but that one could learn something about one’s own relationship to grief and mortality, by attending to the specific and diverse concerns of this community.15

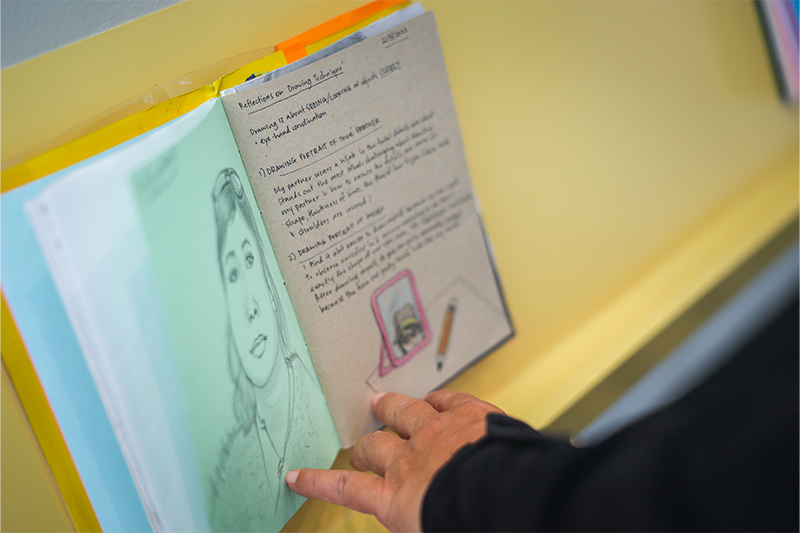

For their visual arts component, they invited artist and educator Dahlia Osman to develop and deliver a series of art workshops for several Malay-Muslim participants of different ages and backgrounds. Over a period of six months, the participating ‘community art-makers’ were engaged in narrative exchange and invited to convey their thoughts about living and dying through journaling, collage, drawings and other mixed media expressions. The culmination of their efforts were then showcased at the BSN venue in Bedok in an exhibition entitled of life and legacy. In a tour held during the showcase, Dahlia and the community art-makers talked about how the whole process had been a moving and transformative one. They shared that the artistic process provided a language – and not necessarily a spoken or written one – that enabled them to communicate their underlying thoughts, fears, regrets and hopes.

Artist and educator Dahlia Osman demonstrates a printing technique to the community art-makers involved in the of life and legacy exhibition (top photo). The public showcase, which was also curated by Dahlia, was a culmination of the participants’ six-month journey together – creating installations, drawings, prints, and journals that expressed their thoughts on personal relationships, grief, and legacy. Bottom photo by Zinkie Aw.

During a reflection retreat held in 2023 to recollect their thoughts about the two-year edition, the BSN creative team alluded to how they were subconsciously aware of the importance of cultural competence, even in the early iterations of BSN. They recounted how they learned from the diverse array of participants’ stories, which made them rethink some of their assumptions and expectations. The team was also aware that they could not be exhaustive in their desire to be ‘inclusive’, as dimensions of difference are far too multiple, even in a single identified community. By looking at differences through the frame of ‘end-of-life’, the team surfaced ‘new’ divisions, such as caregiving responsibilities, gender expectations, family hierarchies. They also learned that participants’ preparedness to broach the subject of death and grief may rely on how these categories may intersect.

Fostering cultural competence collectively: Challenges and opportunities

In summary, cultural competence as fostered and embodied by artists might look and feel different. For some, it is tacit knowledge, developed through a lifetime of immersive practice and groundedness with everyday life, rather than a codified theory or singular framework. It is also knowledge that is developed collectively with others in equal partnership.

To do this might require a reflection on some current practices and hierarchies within the field of arts-based community work. There needs to be time for conversations between commissioners, artists and project managers to discuss how a project should best be supported, just as there should be conversations involving members of a given community about what they want for the project. Ironically, being culturally competent might prove to be the most difficult during the planning stage, where the desire to move things forward is usually prioritised over examining the ‘culture’ and ethos of the project group itself. Here, artists are well-placed to act on their training and instincts – to take courage and provide that prismatic view; to ask questions that get at what is possible, and not just what is pragmatic.

Despite these challenges, arts-based community work is an evolving field that can yield long term benefits of cooperation, mutual trust, and belonging. Where boundaries between differences may be chipped away, new diversities uncovered, and new communities bridging with others. New ways of knowing and doing may be found in the very environments we inhabit, and this requires funding and resources for further investigation and articulation. Through the arts, we can make space for dialogue, listening and understanding. Therein, lies the options we have for reconnecting in this fragmented world; and more crucially, the possibilities.

[1] Charlie Muller and João Paulo de Vasconcelos Aguiar, ‘What Is the Digital Divide?’ [31 March 2022]. Internetsociety.org

[2] ‘Cultural Competence in Health and Human Services.’ [n.d.]. CDC.gov

[3] Brian H. Spitzberg and Gabrielle Changnon, ‘A Synoptic Review of Intercultural Competence Theories and Models’, in SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence, ed. by Darla K. Deardoff (California: SAGE Publications Inc., 2009), pp. 9-13.

[4] Yvette D. Hyter, ‘From Multiculturalism to Critical Consciousness: Updated Concepts for Providing Culturally Responsive Practices at Home and Abroad.’ [28 February 2022]. Pluralpublishing.com

[5] Brian H. Spitzberg and Gabrielle Changnon, ‘A Synoptic Review of Intercultural Competence Theories and Models’, in SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence, ed. by Darla K. Deardoff (California: SAGE Publications Inc., 2009), pp. 7-9.

[6] Peter Vanham, “A Brief History of Globalization.” [17 January 2019]. Weforum.org

[7] Raquel Martin, ‘You’re Doing It Wrong: The Evolution of Cultural Competence.’ [22 February 2023]. Youtube.com/@TedX

[8] Shane Pereira and Mathew Mathews, ‘Singapore, ASEAN, and Cultural Competence.’ [n.d.]. Csc.gov.sg

[9] Allaya Cooks-Campbell, ‘How Cultural Humility and Cultural Competence Impact Belonging.’ [14 February 2022]. BetterUp.com

[10] Justin Lee et al., ‘What is Arts-Based Community Development?’, in The Unique Value of the Arts in Community Development (Singapore: Institute of Policy Studies, 2020), p. 11.

[11] Justin Lee and Jui Liang Sim, ‘Arts-Based Community Engagement in Singapore: Success Stories, Challenges, and the Way Forward’, in Handbook of Research on the Facilitation of Civic Engagement Through Community Art, ed. by Leigh Nanney Hersey and Bryna Bobick (Pennsylvania: IGI Global, 2017), pp. 393-394.

[12] A Guide to Impacting Communities Through the Arts (Singapore: National Arts Council, 2021), p. 2.

[13] Trivic, et al. Assessing the Impact of Bringing Arts into Neighbourhoods. (Singapore: National Arts Council and NUS Centre for Sustainable Asian Cities, 2019).

[14] End-of-Life in the Malay-Muslim Community: Research Report (Singapore: ArtsWok Collaborative and Drama Box, 2020), p. 50.

[15] Zachary Hourihane, ‘Live Well, Leave Well: On Death and Dying in the Malay Muslim Community’, [11 December 2021]. Ricemedia.co.

Cover image: Publicity image of Kembali, a dance performance devised by P7:1SMA. Photo by Zinkie Aw.

All images provided by ArtsWok Collaborative unless specified otherwise.

About Regina De Rozario

Regina is an artist, writer, and researcher investigating artistic practices in Singapore’s public spaces. A recipient of the National Arts Council Arts Scholarship for postgraduate studies, she is currently conducting her doctoral research at the National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University. She is also co-founder of Perception3, an interdisciplinary art duo based in Singapore. Their recent work includes commissioned installations for the Singapore Biennale (2016), iLight Singapore: Bicentennial Edition (2019), and the Singapore Night Festival (2022). As an adjunct educator, Regina is a supervisor with LASALLE College of the Arts’ MA Fine Arts programme, and a lecturer with the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts’ BA (Hons) Fine Art programme where she teaches collective artistic practice and research methods.